The Simon Commission landed in India without a single Indian voice — the response was a sea of defiance

On a grey February morning in 1928, the streets of Bombay burst into an unforgettable display. Thousands pushed forward, waving black flags high against the colonial sky. Their message was as plain as the banners themselves: “Simon, go back!”

It was not the sound of guns but the sight of cloth — dark, fluttering, insistent — that unsettled the British that day. The Simon Commission had come to India to shape its constitutional future, yet it arrived without a single Indian member. An empire already cracking under pressure now faced the shame of being shouted down in its own dominion.

The British plan was straightforward: send a seven-member team, led by Sir John Simon, to assess how India’s constitutional arrangements under the 1919 Government of India Act were functioning. However, the arrogance was astonishing. Seven men, all white and British, were sent to decide the future of a subcontinent.

(Credit: Britanica )

The announcement sparked outrage. At a Congress session in Madras in 1927, leaders committed to a boycott. The Muslim League under Jinnah also opposed it, although some factions, such as the Justice Party and loyalists like Sir Muhammad Shafi, supported it. The central question was unavoidable: how could a Commission determine Indian self-rule without including Indians?

When the Commission’s members disembarked from their ship in 1928, they were met not with garlands but with fury. Across Bombay, Lahore, and Calcutta, protests erupted. Black flags darkened the skies, strikes halted cities, and slogans resonated through the streets.

The colonial state responded with its usual blunt instrument: the lathi. Demonstrators were driven back, blood staining the pavements where they had chanted just moments before.

(Credit: Wikipedia )

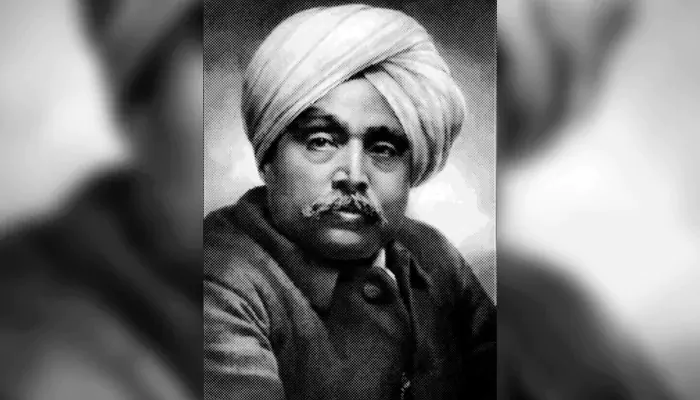

In Lahore, Lala Lajpat Rai — the revered “Lion of Punjab” — led a march against the Commission. A brutal baton charge left him severely injured. He never recovered, dying later that year. His death became a rallying cry for young revolutionaries, including Bhagat Singh, who vowed to avenge him.

Not all engagement with the Commission occurred through street protest. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, representing the Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha, took the opportunity to present the Commission with a report on the conditions of the “depressed classes.”

Credit: Medium

His intervention served as a reminder that India's struggle for freedom was also a fight for equality within its own borders. While most leaders rejected the Commission outright, Ambedkar utilised it as a platform to demand recognition for the marginalised.

Despite the fury it provoked, the Simon Commission proceeded with its work, publishing its report in 1930. It recommended abolishing dyarchy, expanding provincial legislatures, and maintaining communal electorates.

Some of these proposals influenced the Government of India Act of 1935, a milestone that increased provincial autonomy and established a federal framework — the foundation upon which India’s Constitution would later be built.

(Credit: Cultural India )

However, the Commission’s greater legacy was unintended. By excluding Indians, it united factions that rarely agreed. Congress and the Muslim League, despite their differences, found common ground in rejecting it. The slogan “Simon, go back” became a rallying cry for India’s demand to have its voice heard.

The black flags of 1928 were more than mere symbols of protest. They served as a stark rebuke to Britain's arrogance, a reminder that a nation of millions would no longer accept decisions made in its name but without its consent.