How the last Mughal emperor was thrust onto a throne of thorns during the great uprising of 1857

Delhi, May 1857. The sound of war drums and musket fire echoed across the old city. Sepoys, having risen in mutiny against their colonial masters, stormed into the Red Fort. And there, behind the marble screens and faded grandeur, an ageing Bahadur Shah Zafar—more poet than king—was pushed forward as the unlikely standard-bearer of rebellion.

It was not ambition but circumstance that crowned him. At eighty-two, frail and weary, he had neither the armies nor the coffers to sustain a kingdom. Yet, in that fateful moment, the emperor of fading glory became the chosen symbol of resistance, his signature inked onto proclamations that called Hindus and Muslims alike to rise against the Raj.

For nearly five months, Delhi pulsed with resistance. Sepoys dug trenches, citizens joined processions, and rebels declared Zafar the emperor of Hindustan once again. The city that had been the centre of Mughal culture—where poets debated under chandeliers and courtyards resonated with ghazals—now bristled with gunpowder and rebellion.

(Credit: News9 )

But by September, the momentum shifted. The British, regrouped and reinforced, launched their assault through Kashmiri Gate. Superstition influenced events: a solar eclipse on the day of battle kept some sepoys indoors, as they were convinced it was a celestial omen of disaster. The redcoats advanced through partially abandoned defences and into the capital, bayonets gleaming in the sun.

What followed was not victory but vengeance. For four harrowing days, Delhi became what one British officer chillingly called “a city of the dead." Corpses littered the streets. Dogs gnawed at human limbs, vultures staggered away, too full to fly. Men were shot, women driven to suicide, and entire neighbourhoods reduced to rubble.

(Credit: kasmentor)

No age, gender or allegiance could guarantee mercy. Collaborators who had aided the Company were executed alongside rebels. Gallows were erected along Chandni Chowk, where dozens swung at once. Torture was common: flaying, branding, mutilation. Delhi's air was thick with smoke, stench, and grief.

The massacre was not merely of bodies but of a civilisation. Delhi, once the jewel of Indo-Persian culture, lost its patrons, its mushairas, and its very rhythm. The Muslim population—considered the backbone of the rebellion—was expelled en masse. Their houses and mosques were confiscated, and their libraries scattered.

(Credit: The Statesman )

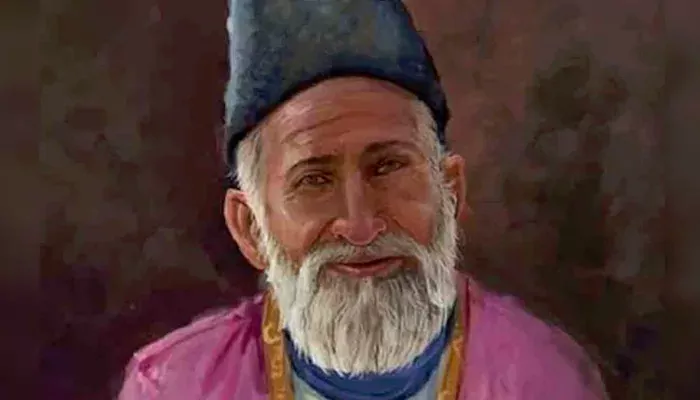

Mirza Ghalib, by pure luck, survived in his Patiala-protected neighbourhood. But his letters reveal the solitude of a city emptied of its soul. “Every grain of dust in Delhi thirsts for Muslim blood,” he wrote in anguish. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the poet-emperor who once dreamed of uniting faiths, was captured, tried in humiliation, and sent off to Rangoon to die in exile—his grave unmarked, his empire erased.

The British began reshaping Delhi. Fort walls were demolished, houses near Jama Masjid were levelled, and mosques were converted into barracks. Where Urdu poets once recited under moonlight, railway lines were laid down. Loyalist traders thrived, while the old nobility faded into obscurity.

And yet, Delhi persisted. It lost its crown but kept its heartbeat. The memory of its suffering became a rallying cry for future generations. When independence finally arrived in 1947, the ghosts of 1857 seemed to whisper through its streets: Empires may crush bodies, but they cannot extinguish memory.