When India stopped asking politely and began to claim its birthright

Imagine the final hours of 1929 on the banks of the Ravi. The winter mist clings to the ground. Thousands of Indians gather, their breath clouding the air as they wait for a moment that would redefine their future. At the stroke of midnight, Jawaharlal Nehru raises the tricolour, its charkha spinning silently on the cloth. Then comes the pledge: India will no longer accept the status of a dominion under the British Crown. Only Purna Swaraj—complete independence—will suffice.

That night was not just symbolic. It was a promise, a collective vow taken under the stars, an oath that ordinary men and women carried back into their homes, their streets, their villages.

Until then, many Congress leaders were willing to accept dominion status—something similar to what Canada or Australia enjoyed. However, younger voices, led by Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, viewed it as a gilded cage. Britain would still hold the keys: the monarch would remain head of state, and Westminster would continue to influence India’s future. For a nation suffering from famines, exploitation, and the memory of Jallianwala Bagh, this was an insult too profound to ignore.

The exclusion of Indians from the Simon Commission and the deaf ear turned to the Nehru Report only strengthened this resolve. Dominion meant compromise. Purna Swaraj meant dignity.

The Lahore Congress session of December 1929 was not a polite debate — it was a storm. Gandhi, always the cautious strategist, preferred a phased approach. But the mood of the nation had changed. Subhas Bose called for a complete break, Nehru expressed the impatience of the youth, and the delegates voted with passion.

When the resolution was approved, it was more than just a parliamentary spectacle. It was the loudest statement yet that the era of petitions and polite memoranda was over. India would no longer plead; it would demand.

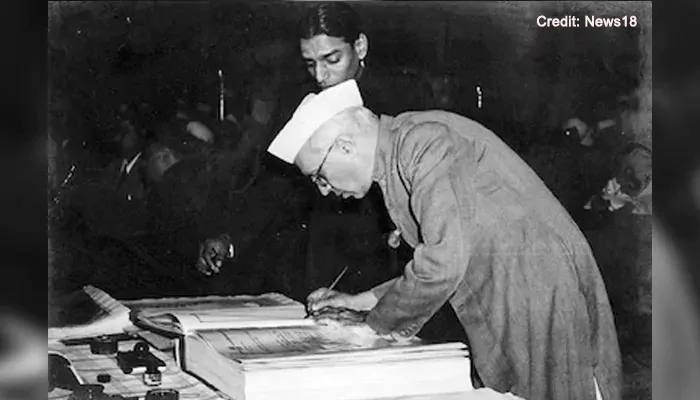

(Credit: Wikipedia )

Congress declared 26 January 1930 as India’s first Independence Day. Across the country, flags were hoisted, hymns of freedom sung, and voices united against the Empire. Schoolchildren, lawyers, peasants, merchants—all took the oath to fight for self-rule. For two decades, the date remained sacred, observed annually as a reminder of the midnight vow.

Later, in 1950, when India’s Constitution came into force, leaders deliberately chose 26 January as Republic Day to honour that first assertion of sovereignty. It was history tying its own knot.

The Declaration of Independence, just 750 words long, reads more like a manifesto than a legal document. It accused Britain of draining India “economically, politically, culturally, and spiritually.” It pledged non-cooperation, including tax resistance. It was terse, unsentimental, and powerful—the kind of writing that sends shivers down your spine.

Though Gandhi and Nehru debated its authorship, its spirit was unmistakably Indian: a people no longer willing to live on someone else’s terms.

(Credit: @priteshshah_)

In hindsight, the midnight ceremony at Lahore seems inevitable. But at that moment, it was bold, even reckless. The British Empire still appeared invincible. Yet, the sight of ordinary Indians, hand in hand, taking an oath of independence, marked the true beginning of the end.

Empires fall not only through wars but also through words—when a colonised people refuse to believe in their own subjugation. On that freezing night in 1929, India ceased to believe in half-measures. From that conviction, freedom became unstoppable.