How one man’s defiance at Barrackpore lit the fuse of a rebellion that shook the empire

On a hot March evening in 1857, at the parade ground in Barrackpore, a single musket shot rang out. It did not topple an empire that day, nor did it ignite an immediate mutiny. But that gun, fired by a restless sepoy named Mangal Pandey, would resonate across the subcontinent — turning a soldier’s anger into a people’s rebellion.

Born in the quiet village of Nagwa in present-day Uttar Pradesh, Mangal Pandey was not initially destined for legend. The son of a modest Brahmin family, he grew up in an India already burdened by the rule of the East India Company.

Credit: Drishti IAS

By the time he joined the 34th Bengal Native Infantry, resentment against the Company was simmering like an open wound. Pay was poor, promotions scarce, and racial humiliation commonplace. Yet the final straw came not from wages or insults, but from the barrel of a new rifle.

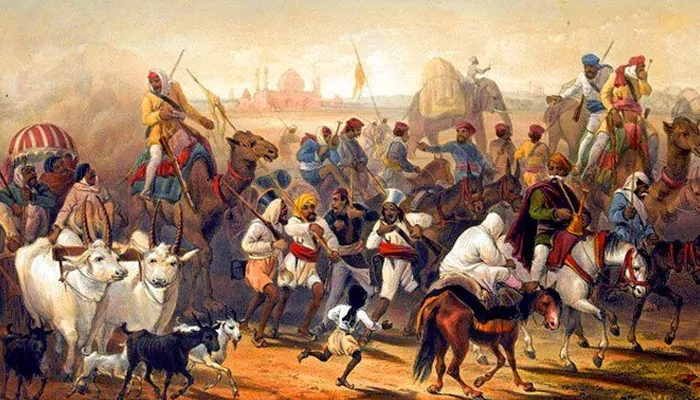

In 1857, the Company introduced the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle, whose cartridges were greased with animal fat. To load them, sepoys had to bite open the cartridge — a gesture that, for Hindus and Muslims alike, was seen as sacrilege.

To Hindus, the cow was sacred; to Muslims, the pig was unclean. Whether true or rumours, the symbolism was devastating. It appeared less an accident of logistics than a deliberate attack on faith.

On March 29, Pandey strode into the parade ground, musket in hand, eyes blazing. Witnesses claimed he had taken bhang or opium, but intoxication cannot explain the fury in his words. He urged his comrades to rise, to cast off the yoke of their British masters. When Lieutenant Baugh, an adjutant, arrived on horseback to quell the disturbance, Pandey drew his weapon. The shot missed the officer but struck his horse. The animal collapsed, and chaos ensued.

Credit: Pinterest

Baugh scrambled up, only to be slashed down by Pandey’s talwar. Sergeant-Major Hewson rushed in, and he too was struck. For a moment, it seemed the entire barracks would ignite. Yet most sepoys stood frozen, unwilling to move against their officers—or against Pandey.

The confrontation ended not in victory but in tragedy. Overpowered, Pandey turned his musket on himself, firing into his chest. He survived the wound, only to be tried and sentenced to death.

Credit: The October Sky

On April 8, 1857, he was hanged, weeks before his scheduled execution, in an attempt to quash any uprising. Instead, his death ignited the flames. Within months, sepoy regiments across northern India rose in rebellion, plunging the Company into its bloodiest conflict.

Mangal Pandey did not live to see the rebellion spread. Nor was he the architect of a grand conspiracy. He was a soldier who acted in a moment of defiance — and yet, history has a way of exalting such sparks. The British mocked rebels as "pandeys," but for Indians, Pandey's name became synonymous with sacrifice and the dream of freedom.

Today, statues, stamps, and films immortalise him as one of India's first martyrs. His act may have been impulsive, but it carried the power of prophecy: the empire could not last forever. In that musket shot at Barrackpore lay the seed of a revolution — proof that even the smallest act of rebellion can reverberate across centuries.