The rebel whose final words became prophecy, and whose legacy still echoes in the hills.

In the cloud-draped hills of Meghalaya, a quiet revolution once stirred. It was led not by kings or generals, but by a man of the people—U Kiang Nangbah. A member of the Jaintia community, he rose to resist British rule during one of the lesser-known but fiercely fought rebellions in Northeast India.

His story is etched in the folk memory of the Khasi and Jaintia people. It is a story of faith, guerrilla resistance, betrayal, and an extraordinary final prophecy.

Though his birth year is unknown, most sources place it in the early 1830s. Nangbah was born in the village of Tpep-Pale in the Jaintia Hills. His people lived by their traditions, which were closely tied to rituals and the natural world. When the British annexed the Jaintia Hills in 1835, they began introducing foreign laws, levying taxes, and interfering in religious practices.

In 1860, British officers disrupted a traditional ceremony at Ialong and imposed a house tax. This intrusion into sacred customs became a breaking point. From that moment, resistance simmered. The community turned to Kiang Nangbah, who was known for his wisdom and integrity. He was chosen to lead the fight at a Dorbar (village council).

Nangbah knew the British were stronger in arms, so he relied on strategy. He organized a decentralized force drawn from different villages—Jowai, Yalong, and others—and trained them in guerrilla warfare. His fighters moved swiftly through the forested terrain, ambushing British patrols, raiding outposts, and burning down government facilities.

They struck by night and vanished by dawn. It was a war of attrition—one that frustrated the British and earned Nangbah the respect of his people. Supplies were stockpiled. Bows, arrows, and swords were forged from local resources. The hills became a fortress no British officer could easily navigate.

By late 1862, however, the resistance began to weaken. The British intensified their operations, bringing in more troops and firepower. During this time, Nangbah fell ill. Seizing the opportunity, one of his men—likely bribed by the British—betrayed his location. On 27 December 1862, he was captured without a fight. He was tried in a British military court and sentenced to death within days. Despite the swift verdict, Nangbah showed no signs of fear. He accepted his fate with dignity.

On 30 December 1862, at Iawmusiang in Jowai, U Kiang Nangbah was led to the gallows. A large crowd had gathered. Before he was hanged, he addressed them one last time: “If my face turns east after death, freedom will come to our land within a hundred years. If it turns west, our people will remain in bondage.” As the trapdoor opened and his body fell, onlookers claimed his face turned east. India would gain its independence 85 years later, in 1947.

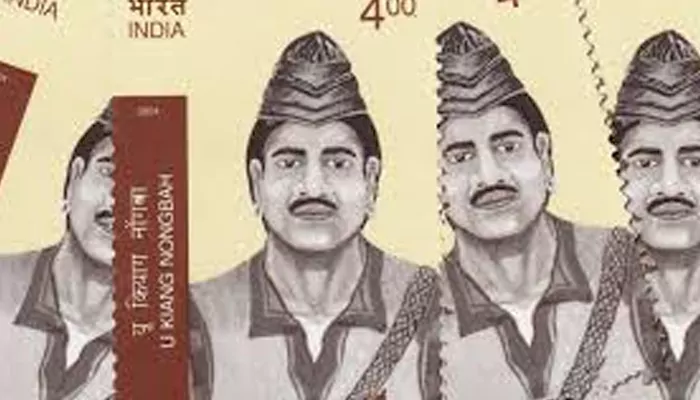

Nangbah’s resistance was crushed, but his legacy lived on. Today, he is one of Meghalaya’s most revered figures. In 1967, a college in Jowai—U Kiang Nangbah Government College—was established in his memory. In 2001, India Post released a commemorative stamp to honour him.

Each year on 30 December, ceremonies and folk songs honour his sacrifice. Yet, outside of Meghalaya, his name remains absent from many history books. Still, his memory endures in stories passed through generations.

U Kiang Nangbah wasn’t born into royalty or military command. He was an ordinary man who chose to stand against oppression. His resistance wasn’t just about fighting colonial forces but defending cultural identity, spiritual freedom, and community dignity. He taught that courage does not require an army. It requires purpose. And a voice willing to speak, even from the gallows. His face turned east. His people never forgot.