Cut off from the mainland, but not from the movement: The untold Story of the Andamans during Quit India.

When Mahatma Gandhi gave his historic “Do or Die” call on 8 August 1942, few imagined that the reverberations would reach as far as the remote Andaman Islands. These islands, tucked away in the Bay of Bengal, were under Japanese occupation at the time. Yet, the spirit of the Quit India Movement managed to find its way into this isolated archipelago, carried through whispers, memories, and the resolve of freedom-seeking Indians. This is the little-known story of how the Andamans, far removed from the Indian mainland, played their quiet part in the struggle for independence.

By the time the Quit India Movement began, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands had already fallen to the Japanese. The British had withdrawn in March 1942, and the islands became one of the few parts of India under Axis control during World War II. In late 1943, Subhas Chandra Bose, leading the Indian National Army (INA), was allowed by the Japanese to visit Port Blair and raise the Indian tricolour. Though symbolic, this act gave hope to many islanders and hinted at a shifting tide.

But beneath this political theatre was a more complicated reality. Japanese forces ruled with an iron fist. Civilians, especially those of Indian origin, were often harassed, arrested, or even executed on mere suspicion. In such times, the idea of “Quit India” became both dangerous and powerful.

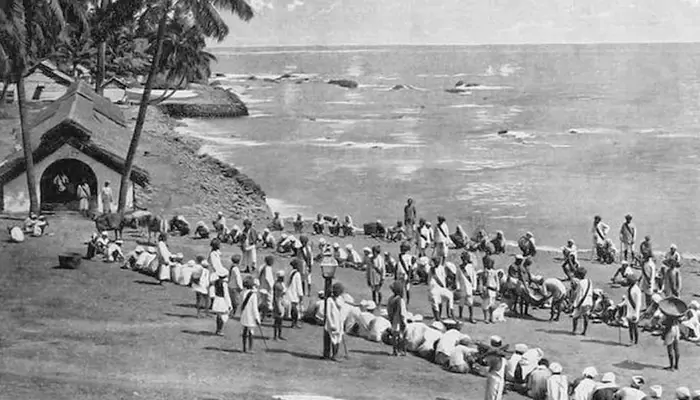

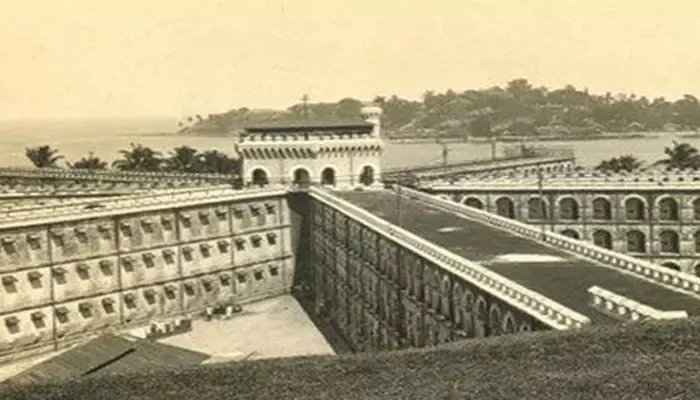

The Andamans had long been a place of suffering for Indian revolutionaries. The Cellular Jail, known as “Kala Pani,” was infamous for housing political prisoners since the late 19th century. Although many of these revolutionaries had been displaced by the 1930s, their legacy lingered in the minds of the islanders.

Residents, some of whom were descendants of convicts and ex-prisoners, carried with them stories of sacrifice and struggle. These tales—passed down in homes and among communities—became the foundation for their silent participation in the national movement.

Under Japanese rule, overt political activity was nearly impossible. Yet, the sentiment behind the Quit India Movement found expression in subtle ways. Islanders boycotted Japanese-sponsored events. They secretly shared radios and leaflets smuggled from the mainland. Even conversations about Gandhi or the Congress became acts of quiet resistance.

A few brave individuals attempted to contact underground INA operatives. Others spread news about Bose’s arrival and speeches, using them to inspire patriotic feelings. Though small in scale, these efforts were acts of defiance in an atmosphere filled with fear.

The Japanese allowed Subhas Chandra Bose to visit the islands in December 1943. During his stay, he renamed the Andamans as “Shaheed Dweep” (Martyr Island) and Nicobar as “Swaraj Dweep” (Self-rule Island). The gesture was symbolic, and Bose was kept mainly from seeing the brutalities carried out by the Japanese forces.

Yet, for the people, Bose’s visit brought mixed feelings. On one hand, he represented their dream of a free India. On the other hand, the harsh realities of the occupation made them cautious. Still, the tricolour flying over Indian land gave many islanders strength and reminded them that they were not forgotten.

After the war ended in 1945, British forces reoccupied the Andaman Islands. Many local stories of suffering and quiet resistance during the Japanese occupation came to light. Though the islanders had not staged large-scale protests like those in Bengal or Bombay, their quiet courage and resilience stood as a powerful chapter in India’s freedom movement.

The Cellular Jail, once a site of horror, was eventually turned into a national memorial. It now stands as a reminder of the countless known and unknown heroes who fought, suffered, and stood firm—whether on the mainland or in distant isles.

The story of the Andamans during the Quit India Movement is a testament to the fact that the desire for freedom knows no boundary. Even in isolation and under foreign military rule, the islanders found ways to contribute to India’s national cause. Their contribution may not have made headlines, but it carved a quiet place in the history of resistance.