Today, the Panchatantra is read in over 50 languages and remains one of the most translated non-religious books in human history

In 570 CE, a Persian physician named Burzoy began an extraordinary journey from the Sassanid Empire to India—not for conquest, but for knowledge. At the request of his king, Khusrow I, Burzoy sought a legendary book said to contain the wisdom of kings: the Panchatantra. What he returned with would transform global storytelling for centuries to come.

The Panchatantra—meaning “five principles” in Sanskrit—was not just a collection of animal fables. It was a political education manual wrapped in wit and allegory, intended to prepare young princes in the arts of statecraft, morality, and survival.

The stories employed talking animals to convey human flaws and virtues. Over time, its tales would be adapted, translated, and absorbed by cultures across continents.

(Credit: Poojn.in)

Although Burzoy’s original Middle Persian translation, Karirak ud Damanak, is now lost, its influence persisted through the Arabic Kalila wa Dimnah, written around 750 CE by the scholar Abd-allah ibn al-Muqaffa. His version, a literary masterpiece in its own right, combined original fables with sharp political commentary, earning him both praise and persecution.

This Arabic adaptation became the main conduit through which Panchatantra stories reached the Islamic world, and from there, the wider globe. In Kalila wa Dimnah, storytelling was not merely a form of entertainment; it became a valuable tool for political education, diplomacy, and moral instruction. Using frame narratives and allegory, this framework would influence generations of writers.

(Credit: Ancient Origins)

By the 11th century, Kalila wa Dimnah had reached Constantinople. There, a Byzantine physician named Symeon Seth translated it into Greek, making it one of the earliest Indian-origin texts to enter Christian Europe. Versions in Hebrew and Old Spanish followed. A Hebrew rendition by Rabbi Joel became the basis for a Latin version by John of Capua, which eventually led to European translations.

The most renowned English version appeared during the Elizabethan era, titled The Fables of Bidpai. That title—Bidpai or Vidyapati—refers back to the Indian sage Vishnu Sharma, the legendary narrator of the original Panchatantra.

The journey from Sanskrit to English spanned at least six languages and more than a thousand years—a notable lineage of literary transmission that influenced global narrative traditions, from Aesop to La Fontaine.

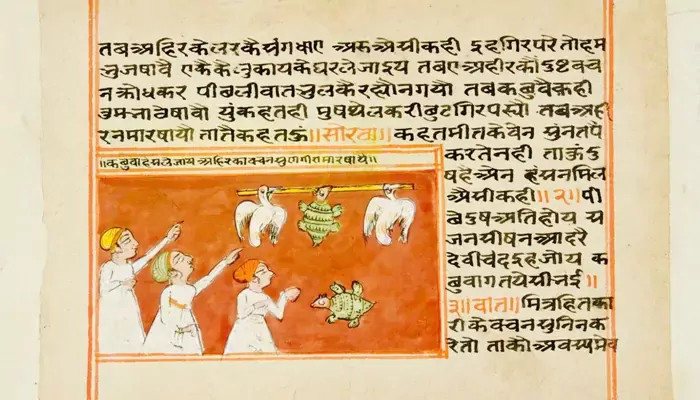

During the rule of the Mughals, Panchatantra gained renewed importance. Emperor Akbar, known for his inclusive outlook, had the text translated into Persian in his court’s maktabkhana (translation bureau). The Sanskrit stories were initially told orally in Hindavi, then translated into polished Persian. The result was: Iyar-i-Danish (Touchstone of Intellect), beautifully illustrated in the Indo-Persian style.

Another well-known adaptation was Anwar-i-Suhaili (Lights of Canopus), written by Husain bin ‘Ali al-Waiz Kashefi in Herat. This work became a staple at the East India Company’s Haileybury College and was later translated into Urdu as Khirad Afroz (The Illuminator of Understanding) for students in colonial Calcutta.

(Credit: OP India)

Unlike fixed religious texts, the Panchatantra developed through each retelling. Its oral origins meant that scribes, scholars, and translators added their own touches, introducing new stories, characters, and moral twists. Jain monks contributed versions, such as the Pancakhnayaka. Stories from the Mahabharata and Kathasaritsagara seeped in, showcasing India’s rich narrative tradition.

The stories were not fixed—they evolved to adapt to political changes, cultural exchanges, and linguistic trends. Each version became a reflection of its time, reshaped to instruct, entertain, and provoke.