What they built was no match for the Taj Mahal, but still, a masterpiece in its own right.

If the British could've erased Shah Jahan’s name from the Taj Mahal and claimed it as their own, they absolutely would have. But since reality wasn't that generous, they came up with the next best thing: build their own version of it in the early 20th century. Confident as ever, they believed British architecture was far superior to anything the Mughals had done. So naturally, they thought their version would outshine the original. However, the only problem was that they didn’t create something new. They tried to copy the Taj Mahal with the same white marble, the same style, and all. And as anyone who has ever tried to replicate a masterpiece knows, imitation rarely ends in glory. If they’d just built something original, it might’ve stood a fair chance. But instead, they aimed for Taj 2.0... and ended up with a beautiful, but clearly second-best, knockoff. Still, what they did build is stunning in its own right. It's one of Kolkata’s most iconic landmarks today. But honestly (and I'm from Kolkata), it’s no Taj Mahal.

In this story, we revisit the British Empire’s ambitious architectural attempt and the spectacular way it missed the mark.

When Queen Victoria passed away in 1901, it wasn’t only Britain that went into mourning. India, too, was expected to grieve the loss of its Empress. Victoria had ruled through a transformative phase of the British Empire, and her death called for a memorial that matched her symbolic stature. Lord Curzon, known for his flair for pageantry and preservation, seized the moment. As Viceroy since 1899, he envisioned a grand structure in Calcutta (then the capital of British India) that would serve both as a tribute to the Queen and as a museum glorifying the British Raj.

#OTD in 1819 Queen Victoria was born at Kensington Palace.

— The Royal Family (@RoyalFamily) May 24, 2018

The only child of The Duke and Duchess of Kent, Princess Victoria became Queen in 1837 and reigned until her death in 1901. pic.twitter.com/EhwN6LDPXp

(Credit: The Royal Family)

But why the Taj Mahal comparison? Because the Taj already stood as a global icon of architectural brilliance and emotion. Curzon, a self-proclaimed history lover who had previously overseen restoration work on the Taj itself, saw a chance to replicate its legacy, only this time, through the lens of British imperial power. The Taj was a monument to love; the Victoria Memorial would be a monument to rule. But there was another key difference: the Mughals had built it from within their own empire. The British, on the other hand, were trying to carve a legacy out of someone else’s land, wealth, and labor. And that was bound to get complicated.

The Victoria Memorial was a logistical and architectural marathon. Construction began in 1906 and took 15 long years to complete, finally opening to the public in 1921. The project was helmed by Sir William Emerson, former president of the Royal Institute of British Architects, with assistance from Vincent Esch. The design aimed to merge British classical architecture with Mughal, Venetian, and Deccani influences, giving rise to what came to be known as the Indo-Saracenic style. The final structure stretched 338 feet in length and 228 feet in width, rising to a height of 184 feet. Topping it all was a 16-foot bronze Angel of Victory, rotating gently with the wind.

Interestingly, the British chose to use the same marble as the Taj Mahal, Makrana from Rajasthan. Transporting over 16,000 cubic feet of this pristine white stone was no small feat; estimates suggest it would have taken a 27-kilometer-long goods train to carry it all. The total cost of the project was a whopping Rs 10 million, a colossal amount at the time. But the twist in the story is that it wasn’t Britain footing the bill. Most of the funding came from Indian princely states and common taxpayers, responding to Curzon’s call for “public contributions.” In essence, Indians were asked to pay for a monument to the very empire that ruled over them. And yes, it didn’t go unnoticed.

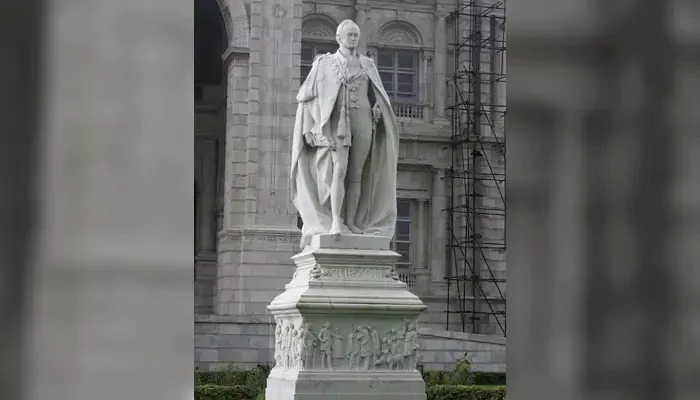

Lord Curzon's statue

Construction wasn’t smooth sailing either. Curzon’s resignation in 1905 following the backlash over the partition of Bengal took the wind out of the project’s sails. There were delays due to soil testing, administrative hurdles, and most crucially, the decision in 1911 to shift the capital from Calcutta to Delhi, which left the memorial somewhat sidelined. Still, by 1921, the structure was complete - a 64-acre complex with sprawling gardens, 25 galleries, and statues of colonial heavyweights like Clive and Cornwallis.

At first glance, the Victoria Memorial does carry the essence of the Taj Mahal. Both are clad in shimmering white Makrana marble, both change hues with the light (pink at dawn, golden by moonlight). The central dome of the memorial rises to 56 meters, somewhat mirroring the Taj’s iconic bulbous dome. The use of symmetry, arches, chattris (domed kiosks), and water features creates a visual familiarity. The gardens, designed by botanist Sir David Prain and landscape architect Lord Redesdale, were inspired by the Charbagh style of the Mughals. Allegorical sculptures representing Art, Justice, and Charity sit atop the dome, nodding to the storytelling style of Mughal ornamentation.

But the similarities are largely cosmetic. The Taj Mahal, commissioned by Shah Jahan between 1632 and 1653, was built as a mausoleum for his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal. Its architect, believed to be Ustad Ahmad Lahauri, infused it with Indo-Islamic design, pietra dura inlays, Quranic calligraphy, and an almost spiritual balance. The Taj is emotionally resonant and is a symbol of eternal love. In contrast, the Victoria Memorial feels like an attempt at grandeur without the soul. Its blend of styles often feels patched together rather than seamlessly integrated.

What ultimately set the two monuments' worlds apart was context. The Taj Mahal emerged from a sovereign empire at its artistic and political peak. The Victoria Memorial, meanwhile, was the product of colonial rule imposed on a restless land. When construction began, the Swadeshi movement was gaining momentum. Indians were rallying against Curzon’s partition of Bengal, burning British goods, and demanding self-rule. To many, a monument celebrating the Raj (and funded with Indian money) was a tone-deaf display of imperial arrogance.

The functions of the two structures differ, too. The Taj Mahal is a mausoleum, housing the graves of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz, drawing millions each year into its contemplative space. The Victoria Memorial, on the other hand, is a museum filled with paintings of Queen Victoria, British military memorabilia, and maps of colonial India. It’s less a place of reverence, more a catalog of empire. While the Taj sees 7 to 8 million visitors annually and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Victoria Memorial draws around 4 million, mostly domestic tourists. It’s beloved in Kolkata, no doubt, but it doesn’t hold the same global or emotional resonance. And its colonial statues and plaques sit uneasily in a country that has long moved on from its imperial past.

The Unveiling of the Queen Victoria Memorial, 16 May 1911

— Empire Aesthetics (@Empireaesth) March 28, 2025

- Sydney Prior Hall (1912) pic.twitter.com/2AgL7eZ7El

(Credit: Empire Aesthetics)

The story of the Victoria Memorial didn’t end in 1921. After India gained independence in 1947, the structure took on a new identity. Galleries dedicated to the freedom struggle and Kolkata’s cultural history were added, gradually softening its colonial edges. The Calcutta Gallery, ironically one of Curzon’s ideas, now showcases the city’s evolution through the centuries. Yet, for all these updates, the building remains a paradox: a colonial monument in a post-colonial world.

For many in Kolkata, it’s simply a beautiful place to stroll, take pictures, or escape the city buzz. But for historians and cultural critics, it continues to raise uncomfortable questions. As historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta points out, the memorial stands “at the core of current intellectual concerns” around how we engage with colonial legacies in modern India.

In trying to recreate the timeless beauty of the Taj Mahal, the British misread the essence of what makes a monument endure. The Taj lives on not just because it’s beautiful, but because it’s personal and rooted in love. The Victoria Memorial, for all its grandeur, remains a symbol of power, not passion. Today, it stands not as a rival to the Taj, but as a reminder of an empire’s misplaced confidence