The Mother Who Dreamed of Swaraj: Understanding Jijabai’s Role in Shaping Shivaji

- Sayan Paul

- 5 months ago

- 6 minutes read

Behind the rise of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, there was his mother, Jijabai Shahaji Bhonsale.

We remember the one who made history, but not the one who stood behind and made it possible. Shivaji, for instance, is celebrated as the great Maratha leader who built the idea of Swaraj. But read more about his journey, and you'll realize that it was his mother, Jijabai, who had dreamed of it first, and who stood by her son at every step. She was his first teacher, his constant guide, and most importantly, the voice that reminded him (at literally every step of life) of his larger purpose. Without her vision and strength, Shivaji’s journey might never have taken shape. And that is why, whenever we speak of Shivaji, we must also remember the name of Jijabai.

So, in this article, we explore how Jijabai’s dream and determination shaped Shivaji’s destiny, and why her role is inseparable from the story of Swaraj.

The World Jijabai Inherited

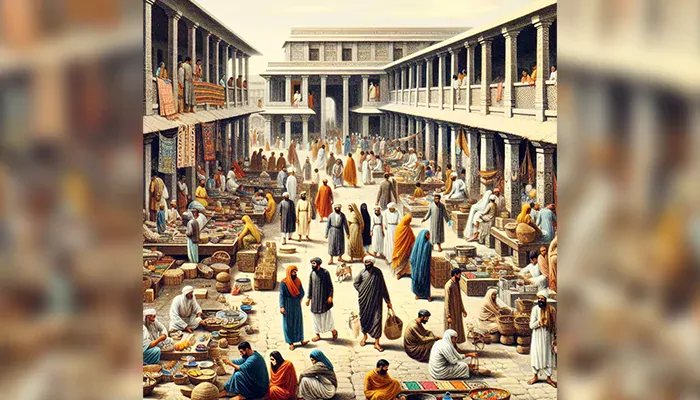

The Deccan of the early 1600s was never still. The Adil Shahis of Bijapur, the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, and the expanding Mughal empire all jostled for dominance. Maratha nobles like Jijabai’s father, Lakhuji Jadhav, tried to survive in this shifting order (serving one sultan, then another), while keeping their local networks alive.

Jijabai was born on 12 January 1598 at Sindkhed Raja, the daughter of Lakhuji and Mhalasabai Jadhav. Through her Yadava lineage, she carried an ancestral pride. At seven, she was married to Shahaji Bhosale during court festivities at Daulatabad.

Shahaji’s own career was a reflection of the era’s volatility. He first served Ahmadnagar, later joined the Mughals in 1630, and eventually entered Bijapur’s service by 1636. Along the way, he received jagirs such as Pune. Jijabai bore him sons, among them Sambhaji in 1623 and Shivaji in 1630 at Shivneri Fort.

Life was precarious, though. The Jedhe Shakavali, a Maratha chronicle, recalls her escape to Shivneri in 1629 during a siege tied to Shahaji’s rebellion. Portuguese merchants at Goa noted the Deccan’s “perpetual wars,” which framed her existence. By the mid-1630s, when Shahaji shifted south to Karnataka, Jijabai remained in Pune, managing the jagir on her own. Contemporary records, both Maratha and English, agree on the point that she ran the estate with firmness and skill.

Planting the Idea of Swaraj

It was in Pune, within the Lal Mahal palace, that Jijabai raised Shivaji during his formative years. She gave him not only stories but also a way of seeing the world. Through the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and tales of saints, she offered lessons on dharma, especially justice, duty, and resistance to tyranny.

The Sabhasad Bakhar, written only decades later, describes her as Shivaji’s moral anchor, who “instilled in him the ambition to found a kingdom.” While the precise words may be stylized, the broader truth is evident that she tied epic values to the immediate hardships of their land.

Now one can imagine the scene. A young Shivaji listens in the garden as his mother recounts Rama’s exile, then gestures toward the fields where peasants bent under taxes. The lesson was plain - power must serve the people, not exploit them. And that conviction later shaped Shivaji’s early raids in the 1640s, aimed not at conquest for its own sake but at establishing swaraj.

From Home to Kingdom

What Jijabai taught at home soon appeared in policy. Shivaji’s governance showed concern for peasants, an insistence on fairness in taxation, and obviously, protection of women and religious sites. Historians have long connected these traits to her influence.

She also guided his decisions during moments of crisis. When Shahaji was imprisoned by Bijapur in 1648, Jijabai urged her son to chart his own course rather than beg for favor. The Sabhasad Bakhar preserves her words, “Do what may secure future good.” Soon after, Shivaji seized the Torna fort, marking the first concrete step toward independence.

Even in questions of administration, she left a mark. Scholars note her role in supporting merit over caste in choosing advisors, a principle that strengthened Shivaji’s state. And while her exact authority as regent during Shivaji’s captivity in 1666 remains debated, English records confirm she managed affairs at Raigad in his absence.

Episodes That Reveal Her Influence

Two episodes, in particular, stand out.

The first came in 1659, before Shivaji faced Afzal Khan at Pratapgad. The Sabhasad Bakhar recalls him seeking his mother’s blessing. Her words were simple: “Sivba, thou shalt be victorious.” When Afzal was slain in the fateful tent meeting (whether by treachery or self-defense remains disputed), her blessing seemed to carry weight beyond ritual.

The second occurred in 1666, when Shivaji traveled to Aurangzeb’s court at Agra. Aware of the danger, Jijabai reminded him of the values she had instilled since childhood. His daring escape months later and triumphant return to Raigad reinforced her role as a source of steadiness. Later bakhars even describe their reunion, with Jijabai recognizing her son through birthmarks despite his disguise—a story part fact, part embellishment, but resonant all the same.

On this day, we remember Rajmata Jijabai, the guiding force behind Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Her unwavering devotion to Dharma and her vision of Swarajya shaped one of India’s greatest rulers.

— Sangam Talks (@sangamtalks) June 17, 2025

Pay tribute to this remarkable mother and nation-builder by reading her inspiring… pic.twitter.com/EaDtrIc8wc

(Credit: Sangam Talks)

History, Legend, and the Gaps Between

However, the historical record of Jijabai is very uneven. Maratha chronicles emphasize her piety and counsel. Mughal sources, focused on Shivaji as a rebel, barely mention her, while English dispatches describe her estate management in matter-of-fact terms.

Over centuries, nationalist memory expanded her role. Folk ballads celebrated her as the mother of swaraj. Stories circulated of the goddess Bhavani gifting Shivaji a sword, or of a youthful oath at Raireshwar temple. Yet such legends find no place in the earliest chronicles. Scholars now sift carefully, recognizing her genuine influence while setting aside later embellishments.