Macaulay’s Minute of 1835: The Blueprint of Modern Indian Education

- Sanchari Das

- 5 months ago

- 4 minutes read

A single policy choice in colonial India created an English-educated elite, opened doors to global knowledge, but also sidelined indigenous wisdom that had thrived for centuries

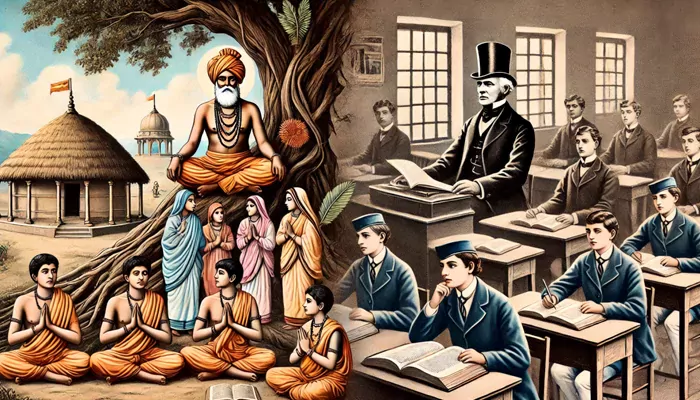

In the early nineteenth century, India’s classrooms looked very different. Knowledge was passed down through gurukuls, madrasas, and pathshalas. Sanskrit, Persian, and Arabic dominated scholarship, while local languages flourished in village schools. Learning was deeply tied to culture, philosophy, and moral values. Then, in 1835, a single document shifted the direction of Indian education. Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Minute on Education laid the foundation for an English-based system that still shapes the country’s schools and universities today.

The World Before Macaulay

Before British reforms, traditional Indian education had remarkable diversity. In rural pathshalas, children learned arithmetic, language, and practical skills. Madrasas trained scholars in theology and law, while tols and gurukuls focused on Sanskrit texts, philosophy, and logic. These institutions were rooted in community and tradition. They did not prepare students for colonial administration, but they nurtured thinkers, poets, and priests. This system was centuries old, but it faced challenges—limited resources, uneven access, and a lack of modernization.

Macaulay’s Radical Proposal

On February 2, 1835, Macaulay presented his now-famous Minute to the Governor-General’s Council. His argument was blunt: funds should no longer support the learning of Sanskrit or Arabic. Instead, they should build a new system centered on the English language. Macaulay declared that Western literature and sciences were superior, famously writing that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” His vision was to create a class of Indians who would act as intermediaries—“Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.”

The English Education Act of 1835

Macaulay’s ideas quickly shaped policy. Lord William Bentinck, then Governor-General, approved the English Education Act of 1835. This act redirected government support away from traditional institutions toward English-medium schools and colleges. Institutions like the Hindu College in Calcutta and new universities in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta became training grounds for future bureaucrats, lawyers, and professionals. The act marked the official shift from classical learning to English education across the subcontinent.

Immediate Changes and the Rise of a New Elite

The transformation was swift. Traditional schools, lacking state patronage, began to decline. Meanwhile, English-medium institutions produced a new educated class. These graduates filled posts in the colonial administration, courts, and professions. They became influential voices in society, often serving as bridges between rulers and the ruled. This group would later play a crucial role in India’s reform movements and independence struggle. Yet, the changes left rural schools and poorer communities behind, widening social and educational divides.

The Downward Filtration Model

The British believed in what they called “downward filtration.” The idea was simple: educate a small elite, and knowledge would trickle down to the masses. In practice, this theory failed. Only wealthy families could afford a modern education. Rural populations continued to rely on fading traditional schools or received no formal education at all. As a result, the benefits of English education were unevenly spread, deepening the gap between urban elites and the rest of society.

The Legacy of Macaulay’s Minute

Nearly two centuries later, the influence of Macaulay’s Minute is still visible. On the one hand, it introduced India to modern sciences, global literature, and a system of higher education that enabled Indians to compete on an international stage. On the other hand, it weakened indigenous knowledge systems and sidelined native languages. The cultural cost was high, and debates continue about the balance between modern education and traditional wisdom.

Conclusion

Macaulay’s Minute of 1835 was more than an administrative decision. It was a blueprint that redefined how Indians would learn, think, and connect with the world. It created opportunities but also left scars on traditional learning. Modern India’s classrooms—whether they teach in English or in regional languages—still reflect the choices made in that decisive year. To understand Indian education today is to look back to 1835, when a new chapter began and an old one was set aside.