How Ice Blocks Travelled Thousands of Miles to Cool British India: Know the Astonishing Story

- Sayan Paul

- 5 months ago

- 5 minutes read

In an age without refrigerators, the British in India still found a way to sip chilled drinks under the scorching sun.

Refrigerators only became common in the early 20th century, but the British were already in India long before that, facing its sweltering summers without a way to keep anything cold. Yet, they still managed to sip chilled drinks, serve ice creams, and host grand parties as if they were back home. How? Well, that’s where the story gets fascinating. Ice didn’t magically appear in Calcutta or Bombay; it travelled thousands of miles across oceans, packed in sawdust and stored in special ships. I know, it sounds almost impossible today. But trust me, it was once a booming trade, built entirely to satisfy the colonial craving for coolness. And it reminds us of how far people would go for comfort.

Before Refrigerators, a Colonial Hunger for Cool

Keeping food or medicine cool in the early 19th century was a constant battle. Mechanical refrigeration would not arrive until the 20th century. In Europe and North America, people relied on winter’s frozen rivers, stored in icehouses through the summer. And in India, families used porous clay pots that cooled water by evaporation, or gathered what little ice could be scraped from shallow pans on frosty nights.

But such methods were no match for the brutal climate of British India. Food spoiled fast, epidemics spread easily, and tempers frayed in the heat. Yet the colonial elite longed for iced drinks at dinner, chilled tonics during fever, and frozen desserts at their grand balls. And also, ice was a symbol. A block glistening on a colonial table signaled wealth, connection to the wider empire, and mastery over an otherwise unyielding land.

Therefore, that hunger sparked a trade few would have imagined possible.

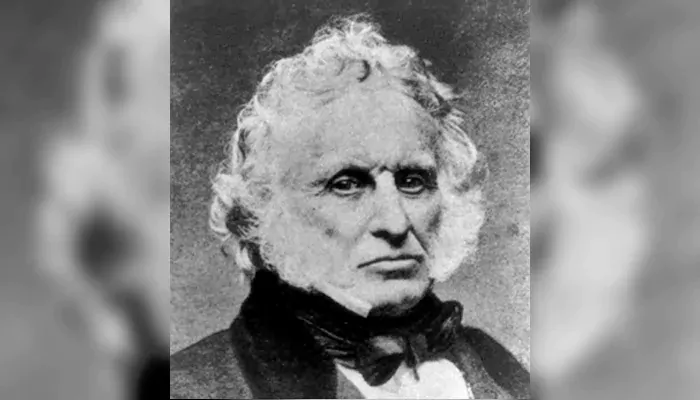

The Man Who Dreamed in Ice

The unlikely mastermind was Frederic Tudor, later remembered as the “Ice King.” Born into a wealthy Boston family in 1783, Tudor abandoned Harvard and spent his twenties chasing schemes. At a picnic one sweltering day, he joked about shipping New England pond ice to the tropics. Everyone dismissed him as mad (but you know, we often confuse genius with madness).

He failed repeatedly (what's success without failure?), first in the Caribbean, even landing in debtor’s prison. But what's important is that he refused to let the idea go. By 1816, he had found success in the West Indies. India, however, remained his true ambition. In 1833, at the age of 50, he finally sent ice east, partnering with merchant Samuel Austin and ship captain William Rogers. “This undertaking has long been my wish,” he wrote in his diary that spring, adding, “an experiment I have been desirous of making for 20 years.”

Tudor worked with inventor Nathaniel Wyeth, who developed horse-drawn ice cutters and efficient packing methods. Rivals soon joined the trade, but Tudor built near monopolies and turned frozen ponds into fortunes.

Moving Winter Across Oceans

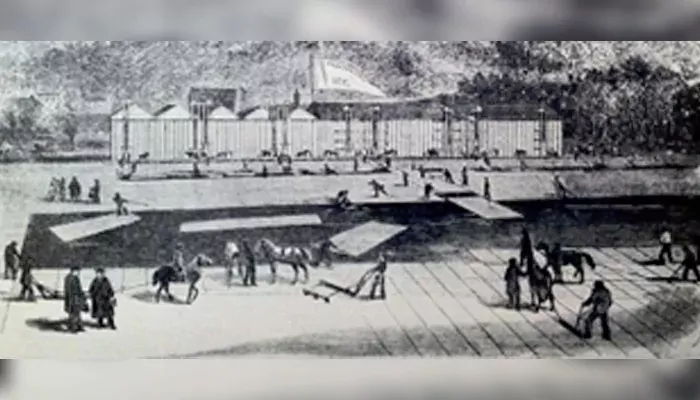

Each winter in Massachusetts, laborers marched onto the glassy surface of ponds such as Fresh Pond outside Boston. Horses dragged special plows across the ice, cutting a perfect grid. Men with saws then carved out massive blocks, each weighing more than 300 pounds.

Getting them to India required ingenuity. The blocks were stacked tight in ship holds, gaps filled with sawdust or hay from nearby mills. Ships like the Tuscany were refitted with double hulls and straw-packed bulkheads. The voyage could last four or five months around the Cape of Good Hope. By arrival, as much as half the cargo might have melted, but enough remained to make the venture profitable.

Once in India, the ice was stored in specially built domed “ice houses,” the first of which rose in Calcutta in 1834, followed by Madras and Bombay. From there, vendors sold ice by the pound - at first an expensive luxury, but gradually affordable for hospitals and middle-class households.

Wonder, Suspicion, and Delight

The first unloading of ice in Calcutta drew a crowd. A man who touched the surface cried out, mistaking the sear of cold for fire. Another asked if it grew naturally in America. For the British, the arrival was greeted with delight. “How many Calcutta tables glittered that morning with lumps of ice!” marveled one magazine in 1836.

Indians, too, had their own traditions of making small quantities of ice in the north. Fanny Parkes, a British traveler in Allahabad, described shallow pans of water left out overnight to freeze under clear skies. But the sheer scale of imported ice was startling. At first, some considered it sorcery; soon it sweetened sherbets, cooled sickrooms, and appeared at public festivities. Ice cream became the marvel of parties. The hard labor of Indian porters, hauling the 300-pound blocks from ship to storage, remained largely invisible in the colonial celebrations.

Profits and Decline

For Frederic Tudor, the gamble paid handsomely. By 1850, he had earned more than $200,000 from the India trade. Ship owners, agents, and colonial officials all took their share. A single cargo might net thousands of dollars, aided by duty-free concessions.

Local ice makers, who had once supplied towns along the Hooghly, found themselves undercut by the cheaper, cleaner imports. By the mid-1850s, the trade reached its peak, with more than 140,000 tons of ice shipped abroad in a single year.

The boom did not last, though. In 1878, the Bengal Ice Company began producing ice mechanically in Calcutta. Other factories followed, and by the 1880s, imported ice had all but disappeared. Soon after, electric refrigeration arrived, and the global ice trade faded into memory.