Here's a look into the popular legend of Shah Jahan’s Black Taj and what history says about it.

We all know Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal, which stands today as the ultimate symbol of love and Mughal grandeur. But there’s a fascinating legend that adds a layer of mystery to this story. It’s said that the emperor planned to build a second, identical mausoleum, this time in black marble, for himself, right across the Yamuna. A “Black Taj Mahal,” they called it. But it was never built. So, did Shah Jahan dream of this shadow twin of the Taj? Or is it just one of those stories that slipped into history like a beautiful rumor? Well, as Nana Patekar says in Welcome, “Ye raaz bhi usi ke saath chala gaya.” Still, if we dig a little into historical records, forgotten ruins, and writings of curious travelers from the past, we may get closer to the truth.

So in this story, we explore where the legend comes from, what the evidence says, and whether the Black Taj was ever more than a dream carved in stone.

The story begins with a Frenchman named Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a gem merchant who traveled through India in the mid-17th century. In his 1676 book Les Six Voyages, Tavernier wrote of a grand plan by Shah Jahan to build his own mausoleum in black marble, opposite Mumtaz’s tomb. He claimed that construction had just begun, but was halted when Shah Jahan was overthrown by his son Aurangzeb in 1658.

Tavernier’s account, however, raises eyebrows. He wasn’t a court historian or architect; he was just a traveler relying heavily on what he heard in the streets and marketplaces. His writings often lack detail and are riddled with hearsay. Still, his single mention became the seed of a myth.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier

In the 19th century, British archaeologists latched onto Tavernier’s tale. A.C.L. Carlleyle and others noticed darkened stones in the Mehtab Bagh and took them as signs of a black-marble foundation. Some even speculated that the two mausoleums were to be joined by a silver bridge - but this idea has been found nowhere in historical records.

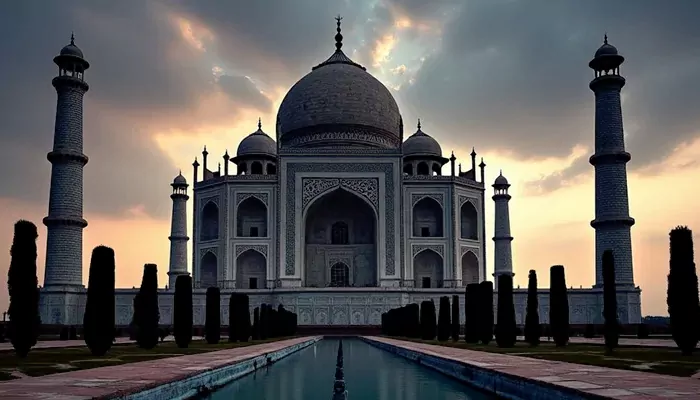

View towards the Taj Mahal from Mehtab Bagh.

Like many colonial-era legends, this one fed into a broader fascination with the "exotic East" and the dramatic story of Shah Jahan's downfall. Over time, the idea of a shadowy twin Taj took on a life of its own.

So, what do Mughal records say about a Black Taj? Virtually nothing.

The most detailed documentation of Shah Jahan’s reign comes from Abdul Hamid Lahori’s Padshahnama, which chronicles the construction of the Taj Mahal between 1632 and 1653. Lahori’s pages glow with details about the monument’s design, the artisans involved, and the emperor’s deep mourning for Mumtaz. But they make no mention of a second tomb across the river.

Other court historians from the time (such as Muhammad Amin Qazwini and Muhammad Saleh Kamboh) also remain silent on the idea. Given the Mughal court’s obsession with recording imperial projects, it seems unlikely that such an ambitious plan would go undocumented if it were real.

Even Aurangzeb’s own correspondence with Shah Jahan, like a 1652 letter about flood damage in the Mehtab Bagh, refers only to repairs in the garden, not to any construction of a mausoleum.

Historian Mohammad Naushad and others have pointed out that if there had been even a foundation laid for such a structure, more than one chronicler would have noticed. Italian traveler Niccolao Manucci, a contemporary of Tavernier, outright dismissed the Black Taj story as marketplace gossip.

At the heart of the myth lies the Mehtab Bagh (literally “Moonlight Garden”) directly opposite the Taj Mahal. Originally designed as a charbagh, or Persian-style garden, it featured fountains, pathways, and fruit trees, all perfectly aligned with the Taj. Its symmetry alone has fueled much of the speculation.

In the 1800s, British explorers believed they had discovered black marble remnants there. These stones, they concluded, were part of the long-lost Black Taj’s foundations.

But modern archaeology tells a different story. In the 1990s, the Archaeological Survey of India conducted extensive excavations at Mehtab Bagh. What they found wasn’t black marble but discolored white marble, stained by time, pollution, and weathering.

In fact, ASI’s 1994 dig revealed no evidence of any structure beyond the garden layout: a central octagonal tank with 25 fountains, and ornamental walkways typical of Mughal gardens. A restored reflecting pool completed in 2006 confirmed what many scholars had long suspected. The garden was designed to mirror the Taj Mahal itself.

Shah Jahan with Prince Aurangzeb, one of the missing pages of the late Shah Jahan Album.

— Timurid-Mughal Archives (@Timurid_Mughal) December 6, 2021

Was this commissioned by Shah Jahan or by Aurangzeb after the war of succession? Aurangzeb looks magnificent, yet Shah Jahan is depicted taller with a larger halo. pic.twitter.com/raLi52xEF7

(Credit: Timurid-Mughal Archives)

As ASI’s Vasant Kumar Swarnkar noted, the Mehtab Bagh was “meant to enhance the Taj’s beauty, not house another tomb.”

So, could Shah Jahan have at least dreamed of building a second mausoleum in black marble? It's not impossible.

Mughal architecture is rooted in symmetry. Just look at the perfect balance of the Taj Mahal complex, with its mosque on one side and jawab (mirror building) on the other. A twin monument across the river would have extended this visual harmony on a grand scale.

Black marble also wasn’t unknown to Mughal builders. Though rare and expensive, it was used in decorative inlays, such as at the tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulah. But creating an entire structure from it would have stretched even Shah Jahan’s considerable resources.

In The Complete Taj Mahal, art historian Ebba Koch argues that the emperor’s vision was centered on the Taj as Mumtaz’s eternal home. The idea of a second tomb simply doesn’t align with the evidence.

Some point to the off-center placement of Shah Jahan’s cenotaph in the Taj as proof that he wasn’t supposed to be buried there. But this, too, is explained by Islamic burial traditions, where the husband is typically placed to the right of the wife. His burial beside Mumtaz was likely always the plan.

Among historians, skepticism far outweighs belief. Ebba Koch dismisses the Black Taj theory as a “romantic myth,” unsupported by any architectural or archival proof. Mohammad Naushad supports this view, pointing to the lack of corroboration for Tavernier’s claim. The ASI’s scientific findings, along with Mughal records and contemporaneous traveler accounts, offer no support for a second Taj. Still, a few scholars leave room for speculation. Wayne Begley, who has studied Mughal symbolism, suggests that Shah Jahan’s love of grandeur makes the idea plausible, even if undocumented. Art historian Georgina Bexon has remarked that the legend aligns with Shah Jahan’s image as a ruler with an eye for the magnificent, if not the practical. However, even those who entertain the idea stress that it remains a legend, not a fact.

Now, why does the Black Taj story endure? Partly, it’s because the Taj Mahal itself feels like a fairy tale in stone. A dark twin across the river fits the emotional drama that the original monument evokes. Tavernier’s vague description was just enough to spark the imagination. British romanticism in the 19th century added further flourish. Local guides in Agra continue to pass the story down, often more for its poetic allure than its historical accuracy.

As Georgina Bexon puts it, “The Black Taj Mahal is a story that thrives on the romance of what might have been.” Undoubtedly, it's a legend that satisfies our yearning for a grander narrative, for hidden truths beneath the surface of history.

As Rabindranath Tagore once wrote, the Taj Mahal is “a teardrop on the cheek of time.” If so, perhaps the Black Taj is the shadow of that tear, and is a beautiful illusion that lingers just out of reach.