Pune's peasants struck back at exploitative moneylenders — and sparked panic across Bombay Presidency

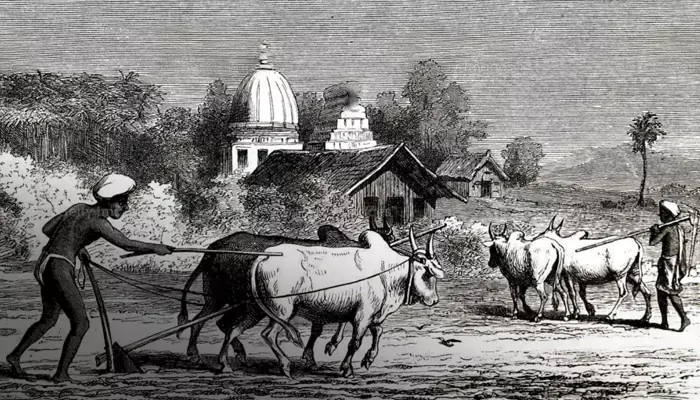

In the scorching summer of 1875, the soil of Maharashtra's Deccan plateau had cracked under drought. But beneath the earth, a deeper fracture was forming. Farmers across the Pune district were being crushed by years of debt. Their crops had failed, yet tax collectors still came knocking. To pay the revenue, they turned to moneylenders. But these lenders, often Brahmin or Marwari sahukars, charged interest rates so high that entire generations were shackled to repayments.

What began as financial desperation soon erupted into defiance.

The colonial revenue system played a central role in this crisis. British authorities, hungry for consistent income, demanded land revenue regardless of crop yield or natural calamities. Unlike the pre-colonial system, which had allowed flexibility during famine, the Raj imposed fixed taxes and enforced them through law. When peasants couldn't pay, moneylenders stepped in. Their terms? Ruthless. Failure to repay meant mortgaging fields, cattle, even homes.

Often, these transactions were sealed in legal documents that the peasants could neither read nor challenge. British courts upheld them, leaving farmers helpless — and furious.

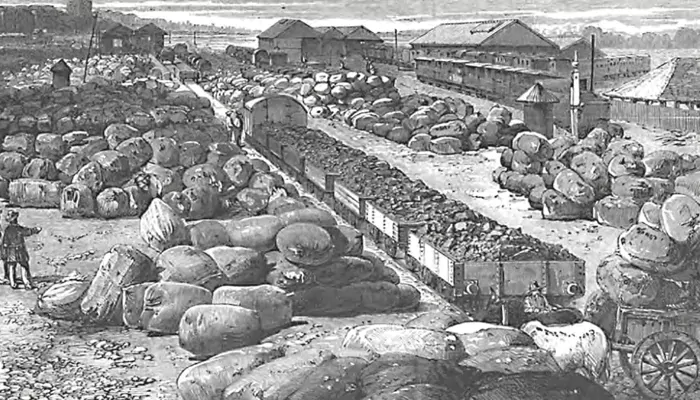

On May 12, 1875, a flashpoint emerged in the village of Supa in Ahmednagar district. A group of farmers, led by local heads and driven by years of oppression, attacked the homes and shops of moneylenders. They didn't harm the lenders physically. But they tore up loan papers, destroyed account books, and burned debt bonds in village squares. To the ryots, these documents were not just paper — they were chains.

Word spread quickly, and in the weeks that followed, over 30 villages across Pune and Ahmednagar districts witnessed similar uprisings.

What made the Deccan Riots distinct was their precision. These were not chaotic mobs. The protests were largely non-lethal and targeted. Farmers carefully identified moneylenders, broke into their homes, and destroyed legal records. Grain hoarded by the sahukars was redistributed. Bonds that had bound peasants to endless repayment were turned into ash.

It was not just revenge — it was a form of rural justice. The ryots had no voice in the courts. So, they delivered verdicts in the language of fire.

As the flames reached more villages, British officials in Bombay were alarmed. District collectors sent telegrams to warn of "serious disturbances" across the countryside. Troops were deployed. Police rounded up hundreds of peasants. Some were tried and sentenced. The administration feared the riots could spread to other parts of the Bombay Presidency, threatening their grip on the rural economy.

Faced with the intensity of rural anger, the British had to act. But not just with arrests — with reforms too.

By 1879, the British passed the Deccan Agriculturists Relief Act. The law restricted the seizure of land for unpaid debts and gave peasants some legal tools to fight back in court. It wasn't perfect, and it didn't undo the past. But it was a clear sign: the Raj could no longer ignore rural distress.

The Deccan Riots didn't just end in suppression. They forced the colonial government to reckon with the fragility of its rural order.

The Deccan Riots were among the earliest organised uprisings against British economic injustice. Long before Gandhi's satyagraha or the rise of national movements, farmers in Pune had already launched their resistance. They had no manifestos, no party backing — just parched land, empty stomachs, and a fire for justice.

Today, their names remain lost in village records, their revolt barely mentioned in history books. But their message endures: when the system fails the tiller of the land, rebellion is never far behind.