A little-known hero led a forest revolt against colonial forest control

In 1910, the forests of Bastar—lush, quiet, and sacred—began to stir. Far from the spotlight of mainstream freedom movements, a different kind of rebellion was brewing. It didn’t come from lawyers or politicians. It came from a tribal belt where trees were gods, and the land was life. At the centre of this uprising was Gunda Dhur, a Dhurwa tribal from Nethanar. With nothing but a bow, a sense of justice, and the trust of his people, he took on the British Empire.

The trouble began when the colonial government tightened its grip on the forests of Bastar. Under the Indian Forest Act, huge areas were declared “reserved forests.” That meant no grazing, no wood collection, no hunting—no life as the tribal people had known for centuries.

For the Muria, Maria, Dhurwa, and other tribes of Bastar, this was more than a law. It was an assault on their identity. The forest wasn’t just a resource. It was home, heritage, and worship. Now, it was fenced off by outsiders.

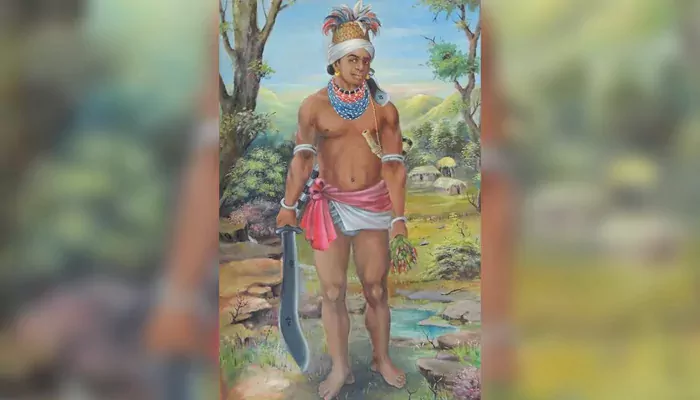

Gunda Dhur wasn’t a king or a scholar. He was a farmer and a hunter, deeply connected to the forest. But what he lacked in status, he made up for with clarity. He saw how unfair the new forest rules were—how they robbed his people of their dignity.

As resentment grew, Gunda emerged as a leader. He didn’t speak in slogans. He stood up, gathered people, and said no. His resistance wasn’t polished. It was raw, honest, and rooted in lived experience.

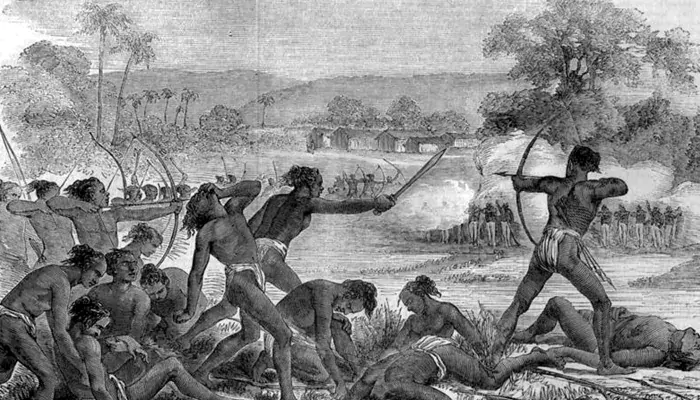

The revolt that followed came to be known as the Bhumkal Andolan—‘bhum’ for earth and ‘kal’ for movement. And indeed, it shook Bastar. Thousands of tribal men and women rose in defiance. They attacked colonial outposts, looted armouries, and released jailed villagers.

Bows and arrows faced down rifles. Tribal war cries echoed through the sal forests. British symbols of power—post offices, police lines, telegraph wires—were destroyed. For a brief moment, Bastar was in tribal hands.

The British response was swift and brutal. Troops poured into the region. Villages were burned. Suspected rebels were jailed or shot. The raja of Bastar, seen as weak and ineffective, was removed. The uprising was put down—but not erased.

Gunda Dhur himself vanished. British records never captured him. There was no trial, no last stand. Some say he melted back into the forests. Others believe he lived quietly until his death, unknown to the broader world.

Across India, names like Gandhi and Nehru are known in every household. But in Bastar, it’s Gunda Dhur whose name carries weight. There’s a statue of him near the Bastar district office. Folk songs still tell his story. He’s honoured on tribal pride days and remembered as a man who stood for justice without ever seeking fame.

Yet, outside Chhattisgarh, few know his name.

Gunda Dhur’s fight wasn’t just about land. It was about voice—about a community asserting its right to exist on its terms. He represents the many tribal struggles that never made headlines but kept the soul of resistance alive.

He didn’t want to rule. He just wanted to live freely. In today’s India, as questions around land rights, forest laws, and tribal autonomy resurface, Gunda Dhur’s story feels more relevant than ever.

His arrows may have rusted, but his courage hasn’t.