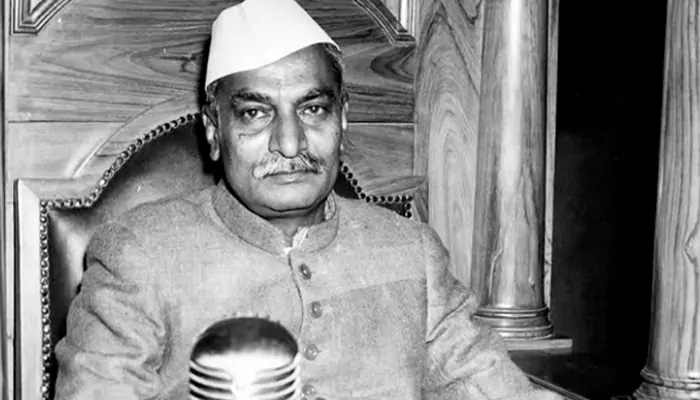

Jan 26, 1950: India's First President Who Lived Like a Monk - Dr. Rajendra Prasad's Rs 10,000 Salary Story

- Devyani

- 21 hours ago

- 5 minutes read

A man paid like a head of state, who chose to live like the village teacher he once was.

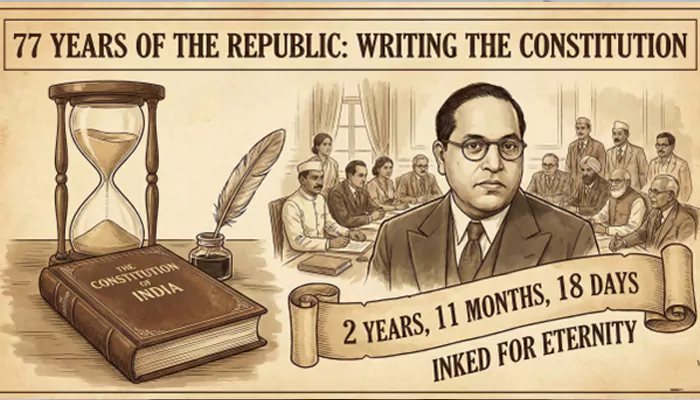

It starts with a number that sounds almost ridiculous now. Ten thousand rupees a month. That was the salary written into the Constitution for the President of India when the Republic came into being on January 26, 1950. In those days, it was a princely sum; enough to run estates, employ staff, and live very comfortably in a newly independent nation still counting every rupee. Yet the man who first received it, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, quietly decided he didn’t need all of it and chose to take only a part, treating the rest almost as if it didn’t belong to him personally.

The Day India Woke Up a Republic

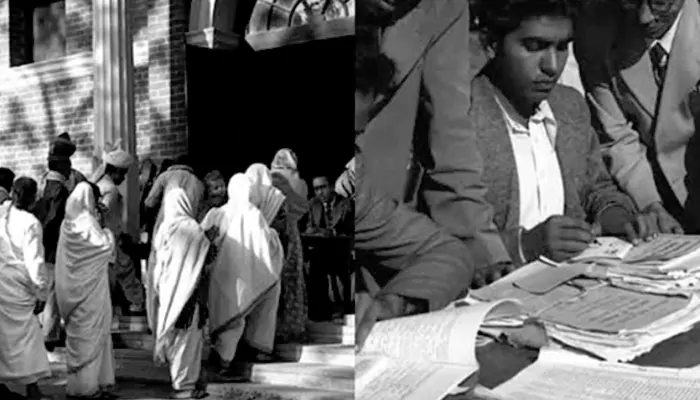

Picture the scene in New Delhi, that January morning in 1950. The Constitution had just come into force; British rule was no more, at least on paper, and a new Republic needed a face and a voice. In the Durbar Hall of the Government House, Dr. Rajendra Prasad took the oath as the first President of India, the ceremony followed by a stately drive to the Irwin Stadium where he unfurled the national flag. A 21-gun salute greeted the tricolour, signalling not just a new system of government, but the arrival of a home-grown head of state who had once been a lawyer, a freedom fighter, and president of the Constituent Assembly.

What many people forget is that on that very day, the palace he stepped into was still called the Viceroy’s House in most people’s minds, a 340-room symbol of imperial power now suddenly repurposed as Rashtrapati Bhavan.

For a man who believed in “simple living and high thinking”, as contemporaries often described him, this must have felt more like a test than a perk.

A Palace with 330 Doors Closed

Here’s the bit that always makes modern readers blink. When he moved into Rashtrapati Bhavan, Rajendra Prasad didn’t behave like an awed tenant in a luxury property; he treated it like a house that needed slimming down. He reportedly ordered around 330 of its 340 rooms to be closed, keeping only a small number in use, just two for his own needs and a handful for guests. His intention, as later accounts note, was to cut costs, reduce extravagance, and strip away the colonial excess that clung to the building. His personal habits matched that decision. He was a staunch vegetarian, banned non-vegetarian food from the Rashtrapati Bhavan kitchen, and preferred to eat seated cross-legged, often on a simple stool rather than at elaborate dining tables.

Relatives and biographers recall him as a frugal eater who liked basic dishes such as lauki and kaddu, the sort of vegetables you’d find in any modest north Indian household, not exactly stereotypical “presidential” fare.

The Rs 10,000 Question

On paper, though, he was not a modestly paid man. The Second Schedule of the Constitution fixed the President’s emoluments at 10,000 rupees per month, a figure that sat far above most public servants’ earnings and symbolised the dignity of the office. Later commentary and reminiscences point out that Rajendra Prasad did not keep the entire amount for personal use, taking only a portion and allowing the rest to flow back into public causes or state expenses, aligning with his long-held commitment to austerity.

To get a sense of the contrast, consider this: by 2022, the President’s salary had risen to several lakh rupees per month, with staff, housing and extensive allowances forming part of the package.

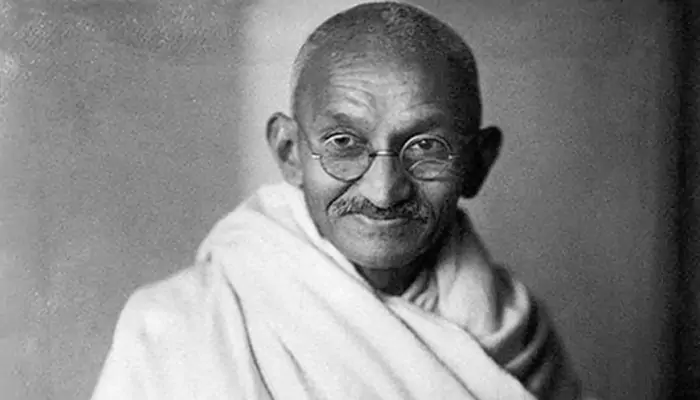

Against that backdrop, the first occupant’s willingness to live like a near-monk within the same palatial walls feels almost surreal, and yet perfectly consistent with the Gandhian ethos that shaped many leaders of that generation.

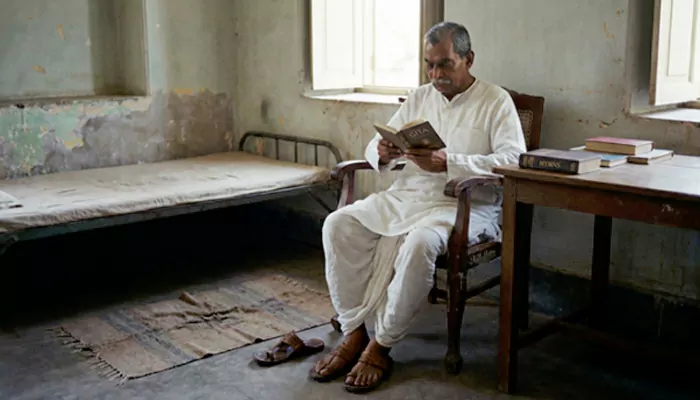

A Monk in Public Office

Accounts from people who knew him, and from those who later studied his life, underline the same thing again and again; Rajendra Prasad tried to ensure that the magnificence of the office didn’t corrupt the simplicity of the person. He reduced personal staff, discouraged unnecessary pomp, and even in retirement, his savings reportedly remained modest, reflecting a lifetime of restraint. Visitors to his later residence describe plain furniture, worn-out shoes, and a prayer corner with copies of the Gita and collections of hymns, more like a scholar’s home than that of a former head of state.

In a time when public life is often judged by motorcades and motorcades by their length, his story feels oddly fresh.

The man at the heart of January 26, 1950, walked into the grandest house in India, shut most of it down, accepted a substantial salary on paper, then chose to live as if he were still that earnest student from Bihar who believed that true prestige lay not in what you owned, but in how lightly you carried it.