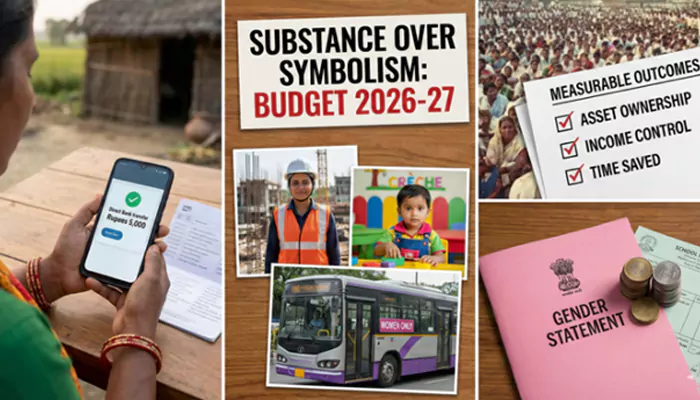

Beyond the Pink Cover: Will Union Budget 2026-27 Actually Deliver Cash for Women?

- Devyani

- 10 hours ago

- 4 minutes read

The Budget book can wear pink, but the only shade that matters to most Indian women in 2026 is the colour of actual money in their accounts.

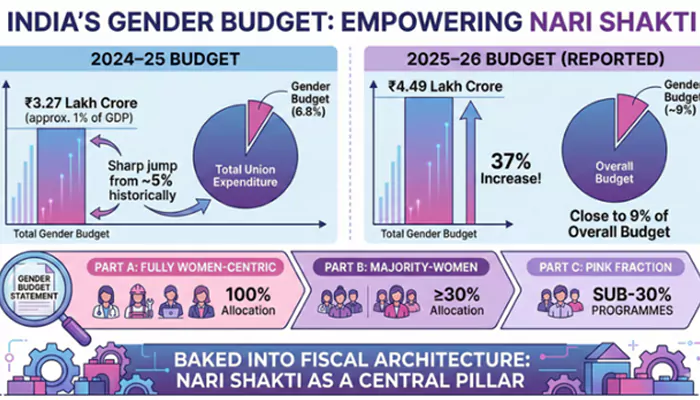

The numbers look impressive at first glance. In 2024–25, India’s gender budget crossed 1% of GDP and touched about ₹3.27 lakh crore, roughly 6.8% of total Union expenditure, a sharp jump from around 5% historically. By 2025–26, that pool reportedly swelled to ₹4.49 lakh crore, nearly a 37% hike over the previous year, with women‑focused allocations now forming close to 9% of the overall budget. On paper, at least, “Nari Shakti” is no longer a side note; it is baked into the fiscal architecture through a detailed Gender Budget Statement that slices schemes into fully women‑centric (Part A), majority‑women (Part B), and even sub‑30% “pink fraction” programmes (Part C).

Schemes with real rupees attached

Some parts of this are not just optics. The Lakhpati Didi push, anchored in Self‑Help Groups, is one of the rare initiatives where women can literally see income change. As of Budget 2024, about 9 crore rural women in 83 lakh SHGs had already helped nearly 1 crore members cross the ₹1 lakh‑a‑year mark, prompting the government to raise its target from 2 crore to 3 crore “lakhpati didis.”

Ujjwala LPG connections, routed in the woman’s name, and continued LPG subsidy allocations, have also eased some of the time and health burden of cooking on chulhas, even if refill affordability remains patchy. Housing schemes like PMAY, now fully counted in the gender budget because titles are often in the woman’s name, quietly shift asset ownership in her favour - a big deal in families where she rarely owns land or a house.

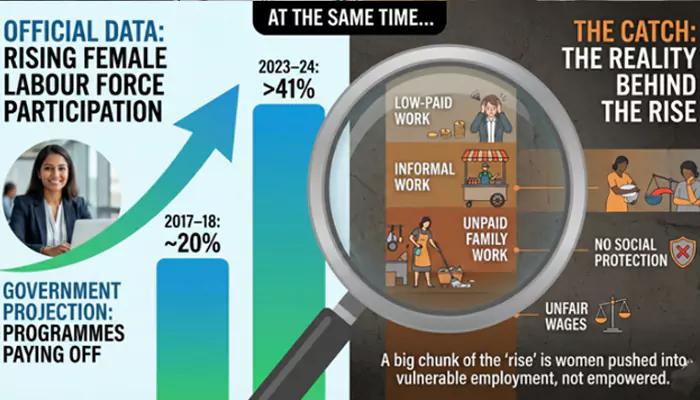

At the same time, the government keeps projecting rising female labour force participation as proof that these programmes are paying off: official data show women’s labour force participation climbing from the low‑20% range in 2017–18 to over 41% in 2023–24. That sounds like a revolution. The catch? A big chunk of that “rise” is women pushed into low‑paid, informal and unpaid work, not necessarily cushioned by social protection or fair wages.

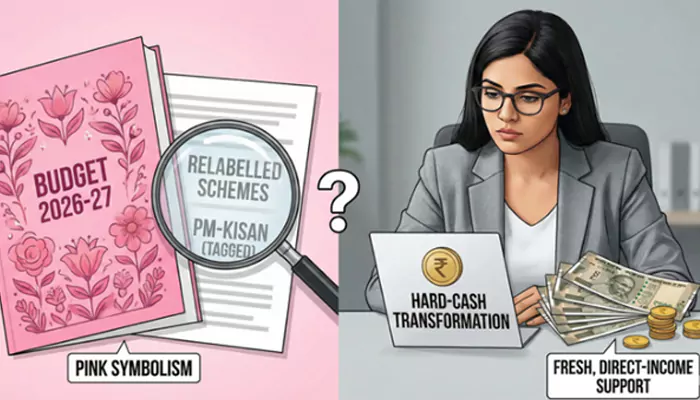

Pink covers, grey zones

So, will the 2026–27 Budget finally move from pink symbolism to hard‑cash transformation? The signs are mixed. Analysts tracking gender budgeting argue that while the envelope has grown, a lot of it comes from relabelling broad schemes like PM‑Kisan or rural housing as “pro‑women” once a portion of benefits is tagged to women, rather than designing fresh, direct‑income support or care‑economy spending. In other words, the pie looks bigger, but the slice that feels unconditional, spend‑as‑you‑wish money in a woman’s hand is still thin.

To really “deliver cash,” Budget 2026–27 would need to go beyond celebrating SHG success stories on the floor of Parliament and push three uncomfortable levers:

- Put more money into direct benefit transfers that land in women’s own bank accounts, not just family‑level subsidies.

- Invest in childcare, safe transport and skilling so that the much‑touted rise in female labour participation is backed by quality jobs, not distress work.

- Tie big flagship schemes to measurable gender outcomes - asset ownership, income control, time saved - not just beneficiary headcounts.

Perhaps the blunt truth is this: a glossy gender statement and a pink‑tinted Budget document make for good headlines; they do not automatically pay school fees, buy LPG refills, or fund that first little business.

Until those line items turn into predictable, autonomous income for women - especially the crores outside salaried, formal work - every new Budget will feel a bit like a festive ad campaign: emotionally stirring, visually on‑brand, but still asking India’s women to clap from the sidelines while the real money moves elsewhere.