From distant plantations and deep poverty, they sent coins that helped change a nation's destiny.

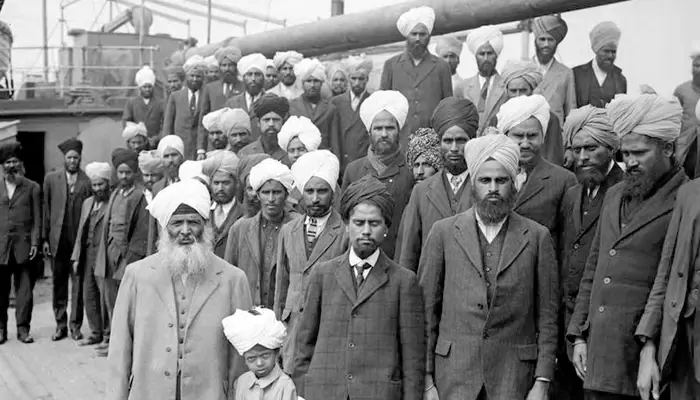

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the British Empire shipped thousands of Indians to Fiji under the indenture system. Recruited with promises of prosperity, they were bound by five-year contracts to gruelling labour on sugarcane plantations. Conditions were harsh. The sun was cruel. Wages were meagre. Many were tricked, and many were coerced.

Yet, thousands of miles from home, India was never far from their hearts. These workers—known as Girmityas—remembered their motherland and helped fund its freedom. Despite their poverty, they contributed whatever they could. A few coins saved from sweat and hunger were offered up for the cause of independence.

So how does a poor labourer support a freedom movement oceans away? In Fiji, it began with coins pooled at temples, homes, and community gatherings. Donations were quietly collected during religious events or festivals—sometimes just a few annas per household.

The money travelled back to India through trusted networks—traders, returning migrants, or sympathetic priests. It funded nationalist newspapers, protest campaigns, and even legal fees for arrested leaders. Their names rarely made the news, but their contributions stitched together a quiet financial lifeline for India's freedom movement.

In one recorded instance, a group of cane workers from Navua pooled Rs. 75—a staggering amount for their means—to support Bal Gangadhar Tilak's legal defence. These were not one-off gestures but part of a steady stream of solidarity.

A turning point came in 1912 when Manilal Doctor, sent by Gandhi, arrived in Fiji. A barrister and activist, he gave Indo-Fijians a political voice. By 1918, he had helped form the Indian Imperial Association of Fiji, which campaigned for local rights and supported Indian nationalism.

Under Manilal's guidance, Fijian Indians passed resolutions condemning colonial violence in India. They raised funds after events like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, sending donations to victims' families and political campaigns. Manilal also pushed for education and political awareness, urging Girmityas to see their struggle as part of India's broader liberation effort.

Religious institutions served as both sanctuaries and nerve centres. Temples, mosques, and gurudwaras were more than places of worship—they hosted fundraisers, charity feasts, and talks on the Indian freedom struggle.

Organisations like the Arya Samaj and Sanatan Dharam Sabha played a key role. Donations could fund a pamphlet in Lahore, a lawyer in Bombay, or relief for families in Bengal hit by colonial repression. Through these quiet channels, faith became an act of resistance.

The press bridged Fiji and India. Newspapers like The Indian Settler and Fiji Samachar regularly carried stories of India's political awakening. Subscriptions and donations from Fiji helped keep radical Indian newspapers afloat.

Even illiterate labourers engaged. They paid others to read aloud, often gathering after dusk to hear updates on Gandhi's Salt March or Nehru's arrest. And they responded—with letters, money, and moral support.

The British authorities in Fiji, wary of unrest, closely monitored such gatherings, censored content, and discouraged political meetings. Even donations were quietly tracked. Yet, Indo-Fijians persisted.

Most labourers had little more than rice for dinner and a worn blanket for the night. Yet they gave. Some even sent money directly to families resisting British rule. They saw India's fight as their own.

There's a moving contrast here—people without rights themselves, giving all they could for someone else's freedom. Their donations were modest but deeply symbolic—gestures of solidarity, sacrifice, and unshaken hope.

India gained independence in 1947. But the Indo-Fijians who helped fund that freedom didn't immediately gain equal rights. Many continued to struggle under colonial and racial laws in Fiji, yet they remained proud of what they had helped achieve.

Few memorials exist to honour them—no statues, no national days. But their story lingers—in faded letters, in temple donation ledgers, and in the memory of a people who gave silently.

They weren't beside Gandhi. They weren't in the headlines. But from distant plantations, they whispered: India must be free. And they backed that whisper with action. Their role deserves more than a footnote. It deserves to be remembered as a foundation.