When a temple door opened, an empire trembled.

No cannons were fired, and no protests filled the streets, yet the British Raj felt the tremors. When the Maharaja of Travancore opened temple doors to the so-called untouchables in 1936, it marked a turning point. Crafted by his Diwan, C. P. Ramaswami Iyer, the Temple Entry Proclamation challenged not just caste but colonial control. It was a royal rebellion—clever, calculated, and quietly revolutionary.

Travancore was modern in many ways—roads, railways, schools. But its society was still tied down by caste. The group known as the "untouchables" was prohibited from entering temples. They stood outside the sacred walls for generations, denying dignity and inclusion. The humiliation was daily, deep, and silent.

Agitations had already begun. The Vaikom Satyagraha in the 1920s made headlines. Dalits protested to walk on roads near temples. The British watched cautiously but did little.

P. Ramaswami Iyer was a sharp man. As Travancore's Diwan (Prime Minister), he had power, vision, and ambition. He saw the caste issue as a moral crisis and a political opportunity. The temple ban was an open wound. Fix it, and you win over the masses. Defy orthodoxy, and you send a message to local elites and the Raj itself.

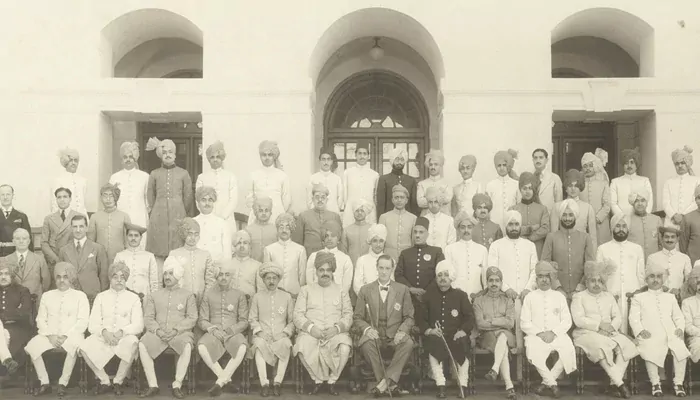

He convinced the young Maharaja, Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, it was time. Together, they changed history.

The royal proclamation was issued on 12 November 1936. Every Hindu, no matter their caste, could now enter temples in Travancore. The announcement stunned the nation.

Supporters cheered. Opponents fumed. Upper-caste conservatives saw it as sacrilege. But the move was firm. The Maharaja had spoken. And behind him stood a Diwan who had played his cards with precision.

Though Travancore was princely, it wasn't free from British oversight. The colonial government didn't interfere in temple matters, but this proclamation felt too big to ignore. It showed the British that Indian rulers could act independently. It hinted at self-rule, courage, and rebellion—not with swords but with pen and paper.

The Viceroy's office took notice. And so did nationalist leaders across India.

Travancore's move inspired others. In places like Cochin and Malabar, pressure grew to follow suit. Gandhi praised the act. Social reformers used it as a rallying cry. If a king could break caste walls, why couldn't a colonized people break imperial chains?

For the British, it was unsettling. This wasn't just religious reform. It was a political awakening—quiet, bold, unstoppable.

The Temple Entry Proclamation was wrapped in morality but driven by strategy. It disarmed critics, empowered the oppressed, and rewrote the script of colonial politics. The Raj liked to think it controlled change. But Travancore proved that real power could come from within.

P. Ramaswami Iyer didn't just open temple doors. He opened the door to a new kind of rebellion that didn't need rifles to shake an empire.

Today, we remember the Temple Entry Proclamation as a landmark in social justice. But it was also a moment of political genius. It showed how rulers could challenge the Raj through reform, that rebellion could wear a royal robe, and that sometimes, the fiercest fight for freedom begins with a quiet act of inclusion.