From hidden shelters to petticoat couriers — the quiet backbone of the Kakori revolt.

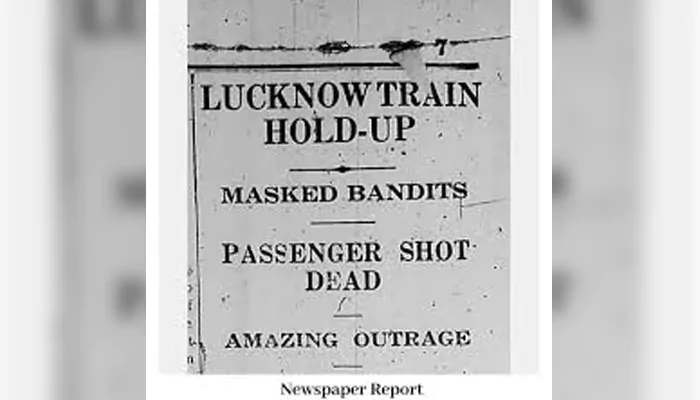

The Kakori train robbery of 1925 is remembered for its daring. Ram Prasad Bismil, Ashfaqullah Khan, and their comrades boldly looted government money to fund India’s freedom struggle. But beneath this headline-grabbing act ran a quieter, deeper current—one built not on bullets, but on trust, secrecy, and sacrifice. A hidden network of couriers, homes, and ordinary citizens made the impossible possible. And at its very heart stood women—unsung, unarmed, but unshaken.

This was not just a heist. It was the lifeline of a revolution. The Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) needed funds to print pamphlets, buy weapons, and move rebels across states. The money looted from the train near Kakori wasn’t the beginning. It resulted from years of coordination among patriots across cities, towns, and villages.

Unknown homes became shelters. Teachers, traders, tailors—all turned sympathisers. These people risked jail and ruin to house revolutionaries. The British police didn’t know their names, but the freedom fighters did. Without them, there could have been no Kakori.

History often forgets the women. But they were there, carrying messages in the folds of their saris, hiding pistols beneath their blouses, cooking meals for rebels on the run. One such name was Rajkumari Gupta. Born in Banda, Uttar Pradesh, she was introduced to the movement by her husband. But soon, her fire burned on its own.

Disguised as an ordinary homemaker, she moved weapons between towns. She once travelled with pistols hidden in her underclothes, a child in her arms to avoid suspicion. When caught, she was disowned by her in-laws. She was sent to jail. But she never broke. Years later, she would say: “We did what had to be done.”

While some picked up guns, others offered shelter. Homes became command centres. In Kanpur, Lucknow, and Allahabad, revolutionaries found beds to sleep in, clothes to wear, and maps to study. Windows stayed shut. Lights flickered low. Meals were passed quietly. Every home had an exit plan.

In many of these houses, women ran the show. They swept around visiting officers while hiding fugitives in cellars. They stirred pots while listening to coded updates. These women knew that if caught, they might never return home. Still, they kept their doors open.

The network wasn’t just about hiding people. It was about information. Messages were tucked inside rotis. Slogans were scribbled in books with invisible ink. Laundry lines became signal posts. A blue sari meant “danger.” A red one meant “safe to move.”

British officers often missed these signs. But Indian women—mothers, sisters, daughters—understood. They passed secrets across courtyards, kitchens, and wells. And they rarely spoke of them, not even decades later.

The Kakori loot funded more than weapons. It helped print bulletins, posters, and leaflets. These papers told people that freedom wasn’t a dream. It was a fight—and it needed them. Many of these were written by Bismil himself, printed in secret presses, and distributed hand to hand by volunteers, many of them women.

Some of these papers made their way into police files, but others reached the right hands, sparking fires in hearts across the country.

Ram Prasad Bismil was hanged. Rajendra Lahiri, Thakur Roshan Singh, and Ashfaqullah Khan were also there. Their bravery deserves every bit of remembrance. But besides their names, we must carve others—those who hid fugitives, passed notes, cooked meals, and carried courage in silence.

The Kakori Conspiracy wasn’t just one night on a train. It was years of invisible work by hundreds who never held a gun but held the movement together. Women in petticoats, families with no fame, homes with no plaques.

They built the revolution that history almost forgot.