How a secret group in Bengal ignited the flame of revolutionary nationalism.

Long before the Salt March or the Quit India movement, Bengal’s streets stirred with a quieter, bolder form of resistance. Founded in 1902, the Anushilan Samiti was more than a youth group. It was a covert training ground for revolutionaries who believed petitions could not free India, but only by bullets and bombs. Their methods were controversial, but their commitment was fierce.

The Samiti was born in Calcutta, in spaces that began as gymnasiums. But these weren’t just places to build muscle. They became places to build courage. Guided by nationalists like Satish Chandra Basu and Barrister Pramathanath Mitra, the group was deeply influenced by the teachings of Swami Vivekananda and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. Physical training blended with patriotism. Vows were taken on the Bhagavad Gita. Youth were taught not only to fight but to sacrifice.

By 1906, the Samiti had grown so large and diverse that it split. One branch continued under the name Anushilan Samiti, while the more militant group came to be known as Jugantar, led by Barindra Kumar Ghosh and supported by Aurobindo Ghosh. Jugantar began publishing a newspaper by the same name—its articles laced with fire and fury, calling openly for an armed revolution.

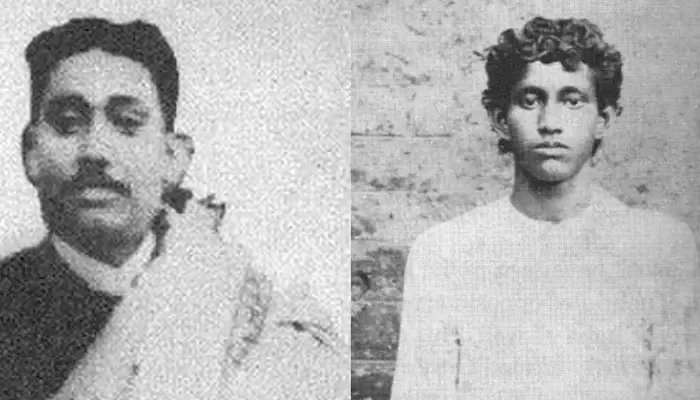

In 1908, two young revolutionaries, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki, tried to assassinate British magistrate Kingsford in Muzaffarpur. Though they missed and accidentally killed two British women, the incident shook the Empire. Khudiram was hanged at 18, becoming a national icon. Secret bomb factories sprang up in Kolkata. Hemchandra Kanungo even travelled to Paris to learn how to make explosives. The Samiti’s reach stretched from Dhaka to Barisal and beyond.

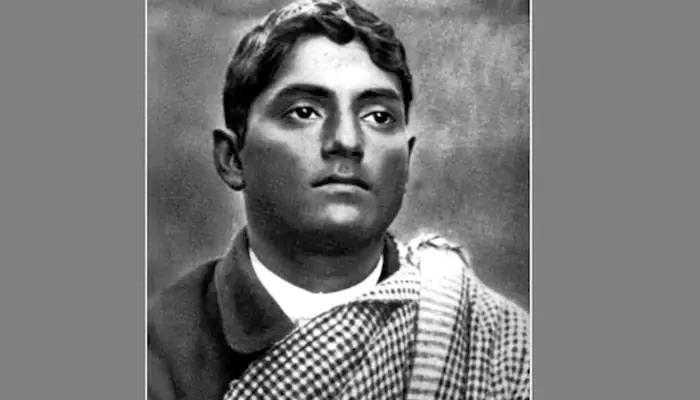

During World War I, Anushilan revolutionaries didn’t sit idle. They saw an opportunity. Along with other radical groups, they became part of the Indo-German Conspiracy—a plan to smuggle arms into India and spark a nationwide uprising. Bagha Jatin, one of the Samiti’s most daring leaders, led this effort. He died in 1915 in a fierce gun battle with British forces near Balasore. His last words: “Amra morbo, jagat jagbe”—We shall die, the world will wake.

The 1914 Rodda arms heist was a masterstroke. A shipment of Mauser pistols and thousands of cartridges meant for the British was quietly stolen by revolutionaries, with help from inside the warehouse. The audacity embarrassed the Raj. Though the Samiti was largely male-led, its ideology inspired women too. Bina Das, trained in the same tradition, attempted to shoot the Bengal Governor in 1932. Pritilata Waddedar, another fiery youth, led an armed raid on a British club in Chittagong.

By the 1920s, the rise of Gandhi’s non-violent mass movement began to overshadow revolutionary groups. Many Samiti members joined the Congress or aligned with newer outfits like the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA). British crackdowns, arrests, and internal fatigue took their toll. Though formally dissolved by the 1930s, its spirit lived on in later movements—especially Subhas Chandra Bose’s INA, which drew heavily from Bengal’s earlier revolutionary energy.

The Anushilan Samiti doesn’t find much space in school textbooks. Its embrace of violence made it uncomfortable for post-independence political narratives. But it lit a fire when the rest of the country was still whispering. It gave India its first taste of militant nationalism and, more importantly, of organised underground resistance.

In remembering them, we remember a truth: freedom wasn’t won by one path alone. It was won by many, and some of those paths were paved with danger, silence, and sacrifice.