When theatre became a weapon and melody transformed into a march for freedom

In 1943, amidst war, famine, and a rising call for independence, IPTA emerged as a force that used art as direct resistance against colonial rule. The Indian People’s Theatre Association wasn’t just a group of performers. It was a movement with the central aim of using theatre, song, and film as tools to challenge the British Raj and inspire collective action.

At a time when censorship and suppression silenced protest, IPTA transformed the arts into a vehicle for political defiance. Their plays were not simply entertainment—they were strategic acts against colonial power, using performance to advance the struggle for freedom.

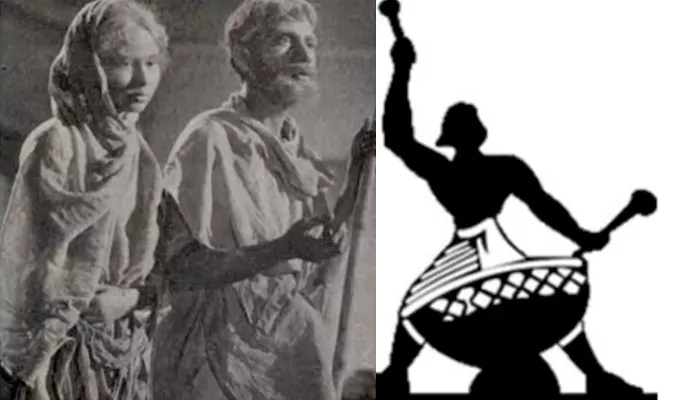

One of IPTA’s most powerful productions was Nabanna (New Harvest), written by Bijon Bhattacharya and directed by Sombhu Mitra. The play was inspired by the Bengal Famine of 1943, which resulted in the deaths of nearly 3 million people. Nabanna confronted the truth head-on in a way government reports did not.

It depicted starving families, failed crops, and uncaring rulers. As the play traveled across Bengal and other regions of India, it sparked an emotional storm. Audiences donated money, food, and even gold jewelry after watching. The play did more than raise awareness—it helped fund relief efforts.

For many, it was the first time theatre spoke their language and told their story.

While theatre formed IPTA’s foundation, film soon became its next frontier. In 1946, K. A. Abbas directed Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth), a film based on Nabanna and other stories from the Bengal famine.

It was a landmark work of realism, created by IPTA members including Balraj Sahni, Zohra Sehgal, and Tripti Mitra. The music, scored by a young Ravi Shankar, deepened the film's emotional power.

The film didn’t follow the formula of escapist cinema. Instead, it portrayed poverty, hunger, and injustice with haunting honesty. It was among the first Indian films to be shown at international festivals, including in the Soviet Union, where it was hailed for its honesty and political clarity.

IPTA didn’t need expensive sets or studios to make an impact. Often, all they needed was a song. Music became a tool of unity, defiance, and inspiration.

Folk forms from Bengal, Punjab, and Maharashtra were reimagined with revolutionary lyrics. Composers like Salil Chowdhury, Prem Dhawan, and Hemanga Biswas created songs that carried the spirit of resistance from villages to city squares.

A re-composed version of Saare Jahan Se Achha, arranged by Ravi Shankar, opened many of IPTA’s events. These songs weren’t just performances—they were mobilising tools, teaching people their rights, history, and power through melody.

Though rooted in India, IPTA’s influences were global. Its members read and translated works by revolutionary poets from Russia, China, and Latin America. But they always returned to the voices of India’s farmers, mill workers, and refugees.

Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, and Marathi plays all found space within IPTA’s fold. From the industrial belts of Bombay to the tea plantations of Assam, IPTA troupes travelled, performed, and listened. Their slogan was simple: “People’s Theatre is the theatre of the people, by the people, for the people.”

This multilingual, pan-Indian identity made IPTA unique. It spoke to India’s diversity without diluting its central message: freedom from oppression.

After 1947, IPTA didn’t dissolve. It evolved. Many of its members went on to shape Indian cinema and music. Balraj Sahni became a leading figure in Hindi cinema. Kaifi Azmi and Sahir Ludhianvi redefined film lyrics. Salil Chowdhury became one of the most influential music directors of the era.

Although the Communist roots of IPTA led to internal splits in later years, its core idea endured. Today, theatre groups like Jan Natya Manch and cultural collectives across India continue to draw inspiration from IPTA, using art to question power and tell people’s stories. IPTA's influence is evident in how contemporary artists address social issues and mobilize communities through performance, ensuring that its legacy continues to shape the cultural landscape of modern India.