A hard-hitting IPTA production, this landmark film portrayed the horrors of the 1943 Bengal famine

When famine struck Bengal in 1943, over three million people lost their lives. Yet the tragedy wasn’t caused by a natural disaster—it was the result of policy failure, war profiteering, and colonial neglect. Amidst this crisis, a group of theatre activists, writers, and filmmakers came together under the banner of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) to tell the story no one in power wanted to hear.

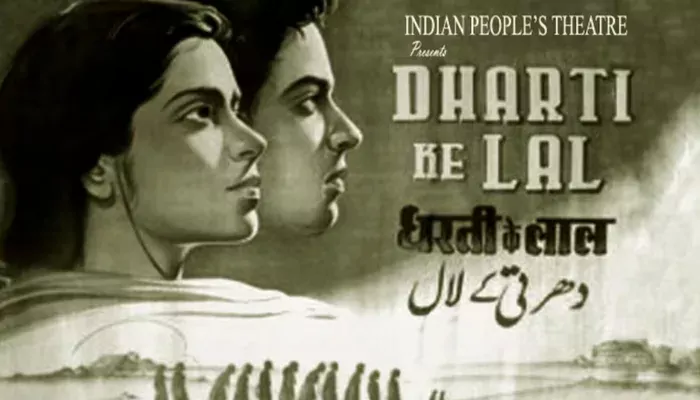

In 1946, they released Dharti Ke Lal—a film that not only documented starvation but also highlighted the plight of the people. It exposed the system behind it.

IPTA, formed in 1942, was never just about performance. It was about a protest. Its members believed that art could mobilize people—and that it must. Bengali playwright Bijon Bhattacharya’s powerful drama Nabanna, based on the famine, moved audiences across India. Around the same time, short stories like Krishan Chander’s Annadata explored the human cost of hunger.

These works became the foundation for Dharti Ke Lal. Directed by journalist and storyteller K. A. Abbas, the film combined IPTA’s theatrical strength with cinematic realism. This was India's first serious social drama on screen—and it didn’t hold back.

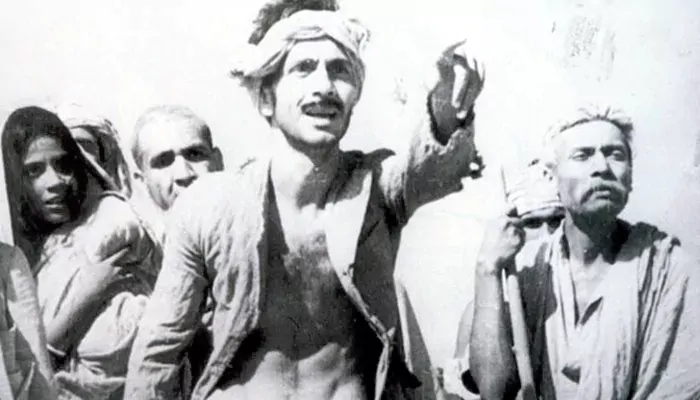

The story centers around the Pradhans, a family of farmers. At first, they are poor but stable. When they sell their rice to afford a family wedding, they become vulnerable to the rising grain prices and heartless profiteers. What follows is a steady, painful descent into hunger.

As famine tightens its grip, the Pradhans migrate to Calcutta. But the city offers no escape. Long food queues, decaying shelters, and heart-wrenching decisions await them. The film shows children begging, women exploited, and men driven to madness. The characters are fictional, but the suffering is real. Every frame is a reflection of what millions endured.

Dharti Ke Lal never points a direct finger at the British administration. But it doesn’t need to. The message is conveyed through the hoarding, the market collapse, absent governance, and cruel indifference. Viewers of the time understood.

The British had diverted food supplies for the war effort. They restricted grain movement and confiscated boats, crippling rural transport. Meanwhile, traders hoarded stocks, and prices soared. The result? A famine that could have been prevented, but wasn’t.

By highlighting these systemic failures, the film made a quiet but firm accusation. It was revolutionary—especially for a film released under British rule.

Many of the cast were IPTA members, not conventional film stars. This included Balraj Sahni, Tripti Mitra, and Sombhu Mitra. Their performances were deeply rooted in their politics—and it showed. No one was acting; they were reliving stories they had witnessed in real life.

The music, composed by the young Ravi Shankar, utilized folk tunes and haunting melodies to lend emotional weight. Songs weren’t just background—they were tools of protest.

Dharti Ke Lal didn’t rake in box office riches. But it left behind something more lasting: influence. It laid the groundwork for parallel cinema in India. It inspired a generation of filmmakers to explore social realism and question power through art.

It was also the first Indian film to be screened in the Soviet Union—proof that its message resonated beyond borders.

In Dharti Ke Lal, IPTA gave Indian cinema its first brush with brutal truth. It was more than a film; it was a document of resistance. It captured not only famine, but the politics behind it. And in doing so, it made sure those lost to hunger were not forgotten.

Nearly 80 years later, its voice still echoes—a reminder that art can confront injustice, even when the system stays silent.