Imagine a desi baniya in dhoti giving hefty loans to British sahibs, saying, “Ja beta, East India Company chala le… aur kuch bach jaye toh kha pee lena!"

When people say India (the subcontinent) was really rich before the British came, what exactly do you imagine? Some gold coins here and there? A few royal palaces? Maybe a king riding an elephant with a diamond-studded turban? Well, whatever it is… multiply that by a thousand. We’re talking obscene levels of wealth, like “if-we-had-Amazon-back-then-it-would’ve-been-Indian” kind of rich. You need numbers? At the time of Shah Jahan, the Mughal Empire had the highest GDP in the world. India alone produced around 28% of the entire globe’s industrial output. Our exports were everything from textiles to shipbuilding (basically, India was the OG global supplier). Especially Bengal. Oh boy, Bengal was so wealthy back then that if real estate on the moon had opened up, some families could’ve booked an entire crater. Per capita income was sky-high, trade was booming, and for many, luxury was just everyday life. I know it sounds unbelievable. But nope, I’m not spinning stories; read a little, and you’ll see these are straight-up historical facts.

Now, amid this mind-blowing prosperity, there was one business family whose wealth makes Mukesh Ambani look like he is still on a student budget. And not just rich folks, these were the people who lent money to the British. Yes, you read that right, a native Indian family giving fat loans to the East India Company. That family was none other than the legendary Jagat Seths. In this article, let’s open the vault and discover who they really were.

“Jagat Seth” wasn’t a name; it was a title that carried weight across empires. Literally meaning “Banker of the World,” it was conferred upon Fateh Chand in 1723 by Emperor Muhammad Shah, a recognition of the family's extraordinary financial clout. For a Mughal Emperor, who ruled vast territories from Kabul to Karnataka, to bestow such a title was an acknowledgment that this family had the power to move economies.

But the roots of this legacy go deeper. The story began with Manik Chand, Fateh Chand’s adoptive father, who had already made a mark in imperial circles. In 1712, after supporting Farrukhsiyar in his successful bid for the throne, Manik Chand was granted the title “Nagar Seth” (Merchant of the City). So that was the first official nod to the family's rising stature. By the time Fateh Chand inherited the mantle, the Jagat Seths had grown into financial powerhouses. They were central to the workings of Bengal’s economy. In today’s terms, if the Ambanis represent corporate influence, the Jagat Seths were their 18th-century equivalent, but with even more direct control over coins, kings, and corridors of power.

Our story starts around 1650 in Nagaur, Rajasthan, with a Jain jeweler named Hiranand Sahu. He traded jewels and saltpeter (a key ingredient for European gunpowder) and started lending money. Soon, he sent his sons across India, like industrious C-suites of the 17th century. One son, Manik Chand, landed in Dhaka, joined the court of Murshid Quli Khan, and later moved with him to Murshidabad, becoming Mint Master. He was literally printing money and commanding respect. By backing emperors to grab thrones, he got both titles and trust. Then came his heir, Fateh Chand, who supercharged the family’s bank.

The Jagat Seths handled minting, tax revenue, public funds, and foreign exchange among others. And they lent to everyone, including the Nawabs, merchants, zamindars, and even the East India Company. Between 1718–1730, chronicles suggest the Company borrowed Rs 400,000 annually from them, an eye-popping amount. And while Bengal thrived, it was the Jagat Seths steering its economic pulse.

Let’s start with the hard numbers and head‑spinning comparisons. By the 1750s, their fortune was pegged at Rs 14 crore, about $1 trillion today. Britain's GDP in the early 18th century was a puny £60–70 million (~$10 billion today). By these estimates, the Seths held 10–15% more wealth than Britain’s entire economy. A British newspaper of the time gushed that they “had more cash than all of Lombard Street”, financial district and all. Ghulam Hussain Khan called their wealth “extravagant fables” because it was almost too far-fetched to believe.

Wealth alone wasn’t enough; it was their political power that swung fortunes. That's where Siraj-ud-Daulah came in 1756, who demanded a staggering Rs 3 crore from Mahtab Chand, Fateh Chand’s grandson. When Mahtab Chand said no, Siraj allegedly got angry. The Seths supposedly helped fund the Battle of Plassey (1757), reportedly giving over £4 million (in modern terms) to back Robert Clive’s coup. A French observer remarked, they “placed the feet of the English on the path” to power. And, well… they did.

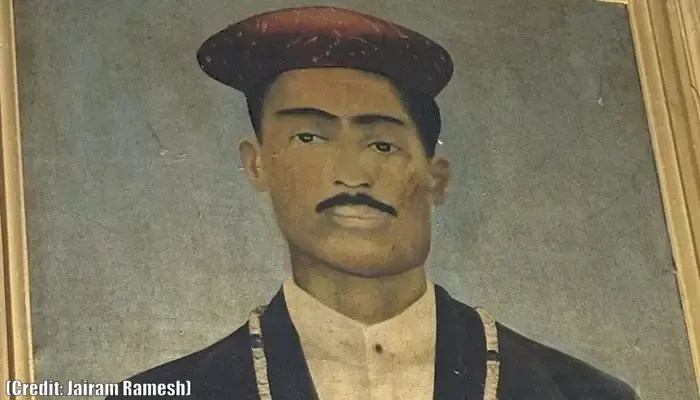

The Jagat Seth house (once Bengal's central bank)

But every story has its twist. Once Britain had what they helped buy, the Seths began losing their grip. The British stripped them of the minting rights, tax control, and hundi system. Then, in 1763, Mir Qasim ordered Mahtab Chand and Swarup Chand executed, throwing their bodies off Munger Fort ramparts. By the 1765’s Treaty of Allahabad, the East India Company had Bengal’s revenue control, and the Seths were mere spectators.

By 1857, the family had faded into obscurity. Their grand palace in Murshidabad remains, which is a museum reflecting a vanished age.

The Jagat Seth's story is of grand riches, king-making, empire-shifting, and eventually, a deal going wrong. Visit their old mansion in Murshidabad today, and you’ll feel the wealth that once dominated the world. Their legacy reminds us that power (and gold) can vanish with time.