Tagore's Trailblazing Women: How a 19th-Century Poet Became an Unexpected Feminist Voice

- Devyani

- 8 months ago

- 4 minutes read

Rabindranath Tagore wasn’t just a poet—he was a feminist ahead of his time. His stories gave 19th-century women agency: widows who dared to desire, wives who walked away, and rebels defying societal norms.

Let’s be real—when you think of Rabindranath Tagore, your mind probably jumps to his soulful poetry, Nobel Prize in Literature, or that iconic song that became two national anthems. But here’s the twist: Tagore was also a low-key feminist icon. Long before hashtags and protests, this Bengali writer used his pen to spotlight women’s struggles, dreams, and quiet rebellions. Let’s unpack how a man born in 1861 became a champion of women’s voices through stories that still feel fresh today.

The Man Behind the Movement: Tagore’s Unconventional Lens

Tagore wasn’t just writing from a vacuum. Born into a progressive family during Bengal’s cultural renaissance, he saw firsthand how tradition and modernity clashed. Women in 19th-century India were often confined to strict roles—marriage, motherhood, and little else. But Tagore’s circle? Think debate clubs, literary salons, and strong female figures like his sister Swarnakumari Devi, a novelist and women’s rights activist. These influences seeped into his work, pushing him to ask: What if women had agency? What if their inner worlds mattered as much as their duties?

Characters That Broke the Mold: From Quiet Rebels to Firebrands

Tagore’s women weren’t just “strong female characters”—they were messy, nuanced, and unapologetically human. Take Binodini from Chokher Bali (1903). A young widow in a society that treated her like a ghost, she’s neither saint nor villain. She schemes, loves fiercely, and demands respect. Then there’s Mrinal from Streer Patra (The Wife’s Letter), who pens a scathing goodbye letter to her husband, declaring, “I am not a doll to be shelved when bored.” Mic drop, 1914-style.

(Bimala in Ghare-Baire)

And who could forget Bimala in Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World)? Torn between her nationalist husband and a charismatic revolutionary, she’s a symbol of India’s own struggle for identity—a woman caught between duty and desire. These characters didn’t just exist; they thrived in their complexity.

More Than Just Rebels: The Heart of Tagore’s Women

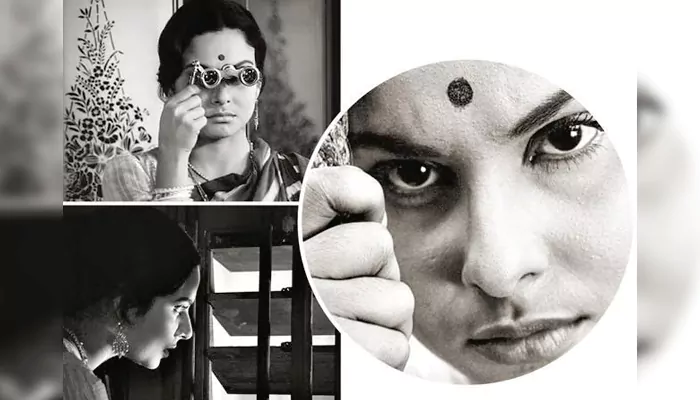

(Charulata)

Here’s the thing: Tagore didn’t write women as “angry feminists” or “perfect victims.” He gave them room to breathe. Charulata, from Nastanirh (The Broken Nest), isn’t just lonely—she’s intellectually hungry, writing secret essays while her husband ignores her. Her emotional affair isn’t framed as scandalous but as a cry for connection. Even secondary characters, like the sharp-witted servant Sudha in Chandalika, challenge caste and gender norms with quiet grit.

Tagore’s genius? He showed that feminism isn’t about grand gestures. It’s in the small acts—a letter, a choice, a silent protest—that change begins.

A Quiet Revolution: Tagore’s Legacy in Modern Feminism

You might wonder, Did any of this actually make a difference? Absolutely. Tagore’s works sparked debates in drawing rooms and classrooms, humanizing women’s struggles decades before feminism became a global movement. Modern Indian writers like Arundhati Roy and filmmakers like Satyajit Ray (who adapted Charulata) credit him for paving the way.

But he wasn’t perfect. Some critics argue his female characters often meet tragic ends—Binodini becomes a nun, Bimala’s life crumbles—a reminder of society’s limits. Yet, even in their tragedies, these women choose their paths. That alone was radical.

So, what’s the takeaway? Tagore didn’t just write about women; he saw them as equals, flawed and fearless. In a world still grappling with gender equality, his stories remind us that feminism isn’t new—it’s timeless. Whether it’s Mrinal’s defiant letter or Charulata’s lonely rebellion, these narratives whisper: Your voice matters.